SRHS

Steamboat Rock Historical Society

WORLD WAR...AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION

THE CRASH...DEPRESSION

When the great depression swept across all of America with devastating force in the early thirties, rural Iowa already knew its effects that now gripped the rest of the country. Droughts were worse in states west and south of us, poor harvests, and the low farm prices of the 1920’s made the farm the spawning ground of general despair that took hold of the entire nation.

The first two decades of the 20th century were relatively good farming years. In the early 1920s the economy going great after recovering from World War I.

Later in the twenties farm prices began to drop, and were not revived until near the end of the thirties. It can be said that the Great Depression began on the farm. When the “Crash” came in 1929, the rural people reminded their city cousins who were just learning of hard time what the people on the land had experienced for several years.

While it can be said that depression began on the farm, in our area most farmland was secure; paid for and left to the sons and grandsons of the original families that settled here in 1855.

Pioneer strength had brought their forefathers through unbelievable hardships to make the land what it was, but this was an entirely new challenge.

Many Iowa farmers in depression times were grateful that they had food on their table. Many in the cities were less fortunate than the farmers. Still not all farmers were as well off, many in Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska and the Dakota’s lost everything due to the worst of drought conditions and couldn’t even put food on their own tables.

Even Iowa farmer’s didn’t eat all that well. Many, even though they had livestock, milk, butter, and eggs feared things would not get better and sold these items for what they could get, or kept them as a hedge against the worst conditions they thought were yet to come.

Charlie Sentman was operating his dry goods business during the depression. In town things were not as good as in the country. Still people had to eat, and Charlie needed the commodities the farmers could provide for those who had a little money to spend for food.

The problem that he had was that many of the farmers weren’t coming into town to buy. They were simply living off what their farms produced.

Charlie went to Des Moines and bought a used auto truck from Younkers Department Store, that they had used for furniture deliveries.

He brought the truck back to Steamboat and outfitted it with an Ice box and shelves, and hired Harry C. Luiken to operate what became known as Sentman’s “Peddle Truck.”

Without the business derived from the peddle truck, Sentmans business may not have survived the depression.

Harry hauled a wide range of merchandise out into the country with one route to the west of town, and a couple to the east, one taking him nearly to Holland. Eggs and butter that the farmers had in quantity were traded for groceries and dry goods including such luxury items as chambre Shirts. The Ice box on the truck was used to bring back large quantities of eggs.

Harry recalled that many of his customers were German, and couldn’t speak English, of if they did, were hard to understand. On one trip Harry stopped at a German farm, and the lady of the house gave Harry her list, and he wrote it down.

Two items that she had requested were corn and Jell-O. When Harry got ready to go to the truck for the items, he asked the lady, what flavor of Jell-O she would like. She replied that she had not ordered Jell-O.

Harry responded by reading her list back to her: Corn; Jell-O…..

“No, no,” she replied. “Jellow corn, I want corn that is jellow.”

Harry went to his truck and brought her yellow corn.

Harry also recalled that tea was a very popular item.

This, is but one of the example of what merchants had to do to keep their doors open and business alive in this difficult time.

There were families that survived months on end on nothing more than eggs and potatoes. The only meat they ate if they ate any at all was rabbits, pheasants and other game they were able to hunt on their land.

The peddler man had been around for years and came with horse and buggy. Actually there were several, the Rawleigh man, the Watkins man, the McNess man, and the Fuller Brush man. They were the early-day version of the Avon lady, except they peddled spices, salves, patent medicines, cough syrup, and painkiller. They still operate in some areas.

They came originally with a horsedrawn rig. They would pull up at the back door, tie their horse, and bring in their cases packed full of the popular needs of those times. They were always welcome and the ladies usually bought. As a matter of fact she would have a list waiting “until the next time the Rawleigh man comes around.” She thought his spices were superior to those in town.

Charlie Sentman simply saw what these companies were doing and played on their success and went after this business himself peddling more of their everyday needs.

We have already heard the story of the Hartman’s and many of the successes Bill Hartman had as a blacksmith, inventor, and well driller. But when Bill died at the beginning of the depression years it presented the family with a difficult situation.

In some writing his daughter Birdie did in 1981 about her brother Willard Hartman she also relates the difficulty the family had holding on to the family farm. The bitter sweet story shows the difficulties that prevailed but also show how families were drawn together to overcome the most difficult of times.

“In 1977 I prepared and had The Gast Scrapbook printed for all descendants of our mother, Ernestine Gast Hartman. When Bill Hartman (Willard’s son) received his copy he told me he wished it contained more, about his father, Willard C. Hartman. He wanted to know more about his dad as a child and young man. About two years ago I started gathering material. I made two trips to Steamboat Rock trying to find someone that went to school with Willard. It seemed that all his old buddies had either passed away or moved away. Then I struck pay dirt in the person of Russell Holmes. He and Willard bad been friends since childhood and he proved to be a great source of many anecdotes and had several snapshots which I have used In this profile.”

“I found, after starting to write, that I could not tell much about Willard without including others. Therefore, this has developed into a family history of sorts covering the years of Willard’s life.”

“Willard was born at home in Steamboat Rock. He was named Willard after Dr. Willard Caldwell who delivered him. I remember two things about that baby, he had the biggest mouth of any child I ever saw and he cried continually.”

“It will be difficult for those of you who knew Willard to believe that as an infant and small child he was a bawl-baby, but he was.”

“Due to the fact that we always had a shed filled with corncobs with which to start the fire in the kitchen range, we also had lots of rats. When Willard was about five or six years old, Dad made a deal with him to pay 5 cents for every rat Willard caught and killed. Willard did so well that Dad started to renege on payment. Thereafter, every time Willard got near Dad he would start to cry and would whine, “I want my rat money”. This got to be a family joke.”

“At our house in Steamboat Rock, we had a long mahogany bannister along the stairway leading to the second story. This bannister was nice and smooth and great for sliding down. One day when Willard was using the bannister for a slide, he slipped off and fell to the hall below. Our mother kept her sewing machine in the hall. Willard’s face struck a corner of the machine before he landed on the hall floor. He didn’t break any bones but did injure one cheek where a small hard lump formed and which never left.”

“When Willard was just a youngster, I’ve no idea how old, the family was out riding in the auto one Sunday afternoon, when a bee flew into the car and stung Willard, I think on the wrist. Within a few minutes his eyes were swollen shut and his face had doubled in size. The venom had gotten into the blood stream and about killed the boy. I don’t remember at this late date whether he was allergic to the sting or whether his serious condition was due to the fact that the poison got into the blood stream immediately. It was a serious matter and Willard about died. Dad kept lots of bees and we “raised” tons of honey but I don’t remember whether or not Willard ever worked around them.”

“For several years Dad was in the honey business. He “raised” a ton or two of honey every season. We had a small “honey-house” in which the honey was extracted and allowed to flow into pails. The pails were then labeled HARTMAN’S EAT MORE HONEY. On one occasion Dad decided to take honey to Marshalltown and sell it to the grocery stores. He asked Ma to ride along and she was glad to do so. Dad asked her how much money she would need to do a little shopping in Marshall and she surprised him by saying she wouldn’t need any.”

“I should say here that for many years Mr. Gralnek, a well known, much respected Jewish junk collector, had called at the blacksmith shop for junk. On the days he called there, he usually ate the noon meal with our family so over the years he became a friend of the family, loosely speaking. Often he would stop at the house and chat with Ma.”

“Now back to the trip to Marshalltown. They stopped at the first grocery store they came to and Dad asked the lady clerk if she would like to stock up on honey. She said they had just put in a supply. Dad assured her that it was a different brand, that he sold only HARTMAN’S EAT MORE HONEY. She went to a shelf and brought back a pail of honey. Sure enough, there it was, HARTMAN‘S EAT MORE HONEY.”

“Of course Dad was furious and asked where she had gotten that brand. She replied, “From Gralnek”. Where did Gralnek get it? Too bad you can’t ask Ma.”

“Then there was the matter of the broken nose. Russell Holmes was there and this is his version of the accident: ‘We were practicing (baseball) just before the game was to start. Willard was the catcher and was warming up the pitcher, so he hadn’t put on his mask or chest protector yet. Someone was hitting balls to the infielders and to the outfielders. A ball was hit to an outfielder and he was supposed to throw the ball home. Willard and the pitcher were still warming up a short distance to the north of home plate. The outfielder threw the ball toward home plate but it was way off mark and it hit Willard in the face. Willard didn’t even see it coming and did a complete backward somersault and bled like a stuck hog. I think Dr. Caldwell was called and came but either that same day or the next Willard’s folks took him to Eldora to Dr. Nuquist.”

“When Willard stayed with John and me In Waterloo Dr. Reuling, a client of our law firm, took an interest in Willard and performed surgery on the nose for free. Apparently It was not a success because Willard had trouble with his nose the rest of his life. He was instructed to use a few drops of argyrol in his nostrils, which he did. His skin became discolored and took on a sort of grey-lavender tone. Wherever he went he rated several glances from passersby, and doctors always though he had heart trouble until an examination proved otherwise.”

“At one time several doctors from the University Hospitals at Iowa City held a clinic in Eldora and the local physicians took their most unusual patient to the clinic to be evaluated. Dr. Nyquist took Willard. The Iowa City group decided that Willard’s skin had been dyed by the constant use of the argyrol.”

“Willard had a lot of natural musical ability. He had a beautiful clear tenor voice. He sang In the High School glee club.”

“Willard also played the cornet or trumpet, I don’t know which. Russell said there was some rivalry between George Potgeter and Willard on the trumpetplaying. Willard thought George needed a lot of practice and George didn’t think Willard even knew how to play the instrument.”

“Russell tells this story about Willard’s dedication to his music. I quote: ‘Steamboat had both a boys’ and a girls’ glee club; sometimes we sang together. KFJB in Marshalltown invited us to put on a concert and, of course, we accepted. The station at that time was located in an old warehousetype building way out on the west side of town. Willard, Orville Lamb and I were dating some student nurses from St. Thomas Hospital in Marshalltown. Willard’s girl was a blond beauty, the daughter of Anderson, a partner in Anderson and Empke paving contractors. These girls were duly notified and we arranged to pick them up the night we were to sing. While the girls’ glee club sang, we three guys would slip out and be in the car with the nurses. Ernie Eckhoff was our lookout man; when the girl-singers finished with their segment of the program, Ernie would come and break up the smooching and we three fellows would rush back in and do our bit. So it went the entire evening and, no, the teacher never caught on.”

“The broken nose ended Willard’s musical career. When he could no longer breathe properly and had a constant postnasal-drip he could neither sing nor play the trumpet.”

“Fannie Potgeter was one of the High School teacher, maybe she was the principal. Russell told me that Willard was her pet. This was borne out by a story Vivian told me: ‘It was Miss Potgeter’s practice, at the end of the term or whatever to exempt students with good grades from taking examinations and to give them the day off. Vivian was one of the good students on this particular occasion, but Willard was not. Viv slid low in her seat where she thought she could not be seen by the teacher and pointed her finger at Willard and “shamed” him, all in fun of course. Well, Viv hadn’t slid low enough … Miss Potgeter saw her, made her stay and take the examinations and let Willard have the day off. Who says the good always triumph?”

“Russell, had several incidents to tell about experiences of the local boys at Pine Lake. Here we go: ‘Willard, Kenneth and I used to go over to Pine Lake in the winter, drive off the road down to the lake in Willard’s dad’s Model T homemade pickup; start at the west end of the lake, get the truck going east as fast as we could, then slam on the brakes. This would cause the truck to go ’round and ’round and ’round. Then we would head to the west and repeat the performance.”

“Just after Pine Lake was constructed my cousin was visiting me. He had always gone swimming in Clear Lake which had a gradual, sloping beach before one reached deep water. At that time there wasn’t much beach at Pine Lake, so the water near the shore was deep.

“Willard, Orville Lamb, my cousin, and I decided to go to Pine Lake to swim.”

“My cousin was the last to get into his swimming suit and the rest of us were already in the water when he ran out pell mell… into deep water and into deep trouble. I went to his aid and before I could help myself, my cousin had me down with his legs in a scissor hold on my shoulders and neck. I had studied in the 8th grade hygiene that if you were ever involved in a situation like this, the best thing to do is to double up your fist and hit the other party in the stomach, which would probably cause that person to relax momentarily, so one could escape his grasp. So I doubled up my fist and swung as hard as I could. However, unknown to me Willard had come to my rescue and instead of hitting my cousin I hit Willard smack in the face. Meanwhile, Orville Lamb had gotten my cousin out of the water. Needless to say, that ended our day at Pine Lake.”

“Here is a real “fish story” that Russell told of Willard, Robert Ruppelt, Junior Ruby and Russell Holmes: ‘The State decided to seine the rough fish out of Pine Lake so we decided to go and watch. They would just throw the fish up on the bank and let people have them for free. People were grabbing them like mad so we got the bright idea of taking some back to Steamboat and telling the folks that we caught them up at Peters Hell Hole near Hardin City. Skinny Star was a great carp fisherman and when he saw all those fish he wanted to know why we hadn’t taken him along. He didn’t quite believe our story. He finally phoned Mrs. Ruby and asked for Junior. She told him that Junior had gone to Pine Lake with some boys to watch them seine. Of course that spoiled our story. We had 9 fish and they weighed 99 pounds.”

“Dad had a lot of confidence in ‘Willard. He would never let Orlo drive the car, but Willard could have it almost any time and invariably he had car trouble of some kind. Dad even let Willard take the car to Des Moines for two or three days during a basketball tournament.”

“The Maxwell was parked on an Incline in front of the house. Willard looked out an upstairs window and saw the car start to roll down the road. He performed a most spectacular feat by climbing out the window onto the porch roof, sliding down a post running down the road and stopping the car just before it plunged into a deep ditch.”

“I quote some more from Russell Holmes: ‘Willard and I were usually always together after we started to school, probably because we lived In the same direction. We usually went to Sunday School together at the Congregational Church. I would look out an east window of my home and watch for Willard to come along and then we would go on together. One time he didn’t show up so I finally went alone. I thought perhaps he was sick, so later I went up to the Hartman house to find out. His mother said he wasn’t sick but was up in his room and that I could go up, which I did. Now, I love popcorn but I couldn’t hold a candle to Willard. There he was in bed with a dishpan full of popcorn reading a Wild West Magazine. I think we were in High School then, but maybe not. Anyway, Willard said “See my new rifle there behind the door?” He told me to go ahead and try it as it was loaded. It was a 22 caliber. It was summer and the north and west windows were open. I looked out to the west and there was Lou Johnson’s house; I looked to the north and there was. Henry Johnson’s house, oh, I said I couldn’t try it because the bullet might ricochet. Whereupon Willard told me to shoot it into the wall, so I did! And they say that today’s kids have no common sense.”

“Russell didn’t say what happened when Dad Hartman found the hole in the wall.”

“While Willard was In school he spent some of his vacations helping Dad on the well drilling rig. I am writing Willard’s story but this seems to be a good time for another of Russell Holmes’ stories about the Hartmans. ‘When your dad was in the well drilling business they were drilling somewhere east of Ackley. They had started home, Kenney and Willard in the front seat driving. Your dad always sat In the back of the truck with his legs dangling. They passed a bum hitchhiking along the road and your dad yelled for the boys to stop. The bum came running and jumped up beside your dad. The Hartmans always had a big box of tools with them and the box was painted red. Every once In awhile your dad would say something like, “Slow down or you’ll blow us all to smithereens. Finally the bum asked what was in the red box and Bill told him it was full of TNT and that they were on their way to blow up the Ackley bank. The two boys took the hint and when they got to the edge of town where they should turn south to Steamboat, they drove right up town and stopped at the Ackley bank. Even before the truck stopped, the bum jumped down and was off and running. All the Hartmans saw of him were the soles of his shoes as he hightailed it out of town.”

“Willard spent some vacation time with John and me in Waterloo, looking for a job. He did work at both Raths and Deere’s. His job at Raths was to grip a cheesecloth bag, keep it open at the end of a chute, and catch the ham as it came hurling down. By the end of the day Willard’s knuckles were raw and bleeding where they rubbed against the rough sack. That job didn’t last long. Then he went to Deere’s and to hear Willard tell It, he spent most of his time on the flat roof of one of the buildings trying to keep out of sight. That job didn’t last long either.”

“I always considered Willard a strong character. He did what he had to do regardless. One instance of this occurred when he was in High School or maybe Junior High. He had a very large St. Bernard type dog about the size of a pony. It wasn’t a family pet, it belonged to Willard and no one else. They were together constantly. It was caught killing sheep and had to be destroyed. Willard wouldn’t let anyone else do the job, he took it out and shot it. That took courage. I was there when he came back carrying his dead pet in his arms. I have never forgotten it.”

“Willard was visiting John and me in Waterloo one winter when we lived on Riehl Street. I don’t know how he happened to be with us in the winter, but he was. I had to work until noon on Saturday and on this particular day a blizzard was in progress. I had hitched a ride home from work and we got stuck in the snow and I had to walk about half a mile or so. When I finally staggered into the house there was gloom all over the place. Our little puppy had distemper (no shots for it in those days) and had to be put out of its misery. Willard was the good guy who took the little creature to the basement and shot it while John and I stayed upstairs with our hands over our ears, crying.”

“The last summer before Dad died, Willard and some of his Steamboat Rock buddies got a job with Bell Telephone Co. They called their employer “Ma Bell”. I don’t know what the boys did but they worked outdoors and had to room and board away from home. This was great fun and those boys really lived it up. Willard talked often of this experience and, undoubtedly, those carefree weeks were some of his most pleasant. He didn’t realize it then but they were to be the last truly carefree days of his life.”

“When this summer job was over I phoned Willard to find out if he had saved enough money to pay his tuition at Iowa State Teachers College at Cedar Falls. If so, he could stay with us. He had about $75.00. I called the Registrar’s office at Cedar Falls and I learned that the $75.00 would cover the tuition. So Willard came to live with us and go to college. I don’t remember how he got to Cedar Falls and back, but probably on the old trolley.”

“John and I lived in upstairs “light housekeeping” rooms on Logan Avenue. The owners of the house lived downstairs. We had a little bathroom which at one time had been a closet, and a kitchenette. The kitchenette was next to the bathroom, had no sink or running water so we had to draw water from the bathroom for use in the kitchen. At that time it didn’t seem at all inconvenient. John and I had a bedroom, and a previous bedroom had been converted into the living room. The couch in the living room was what was known as a sanitary cot. The sides could be folded down during the day and raised at night to make it wider. The springs were part of the cot. but it had no mattress. However, the landlady supplied a pad of some kind. That was the bed Willard slept in.”

“Willard got home from Cedar Falls before either John or me. He would peel the potatoes for supper and pop a pan of corn for evening. He took care of his bed and helped with whatever work there was. He did his share.”

“At the time John and I were married, John had a new overcoat in the most popular style of the day, very long, navy blue, and double breasted. Willard didn’t have an overcoat to wear to school, so he wore John’s. I have never been able to understand how John, who was small, and Willard who was just the opposite, could both wear the same coat and both look OK. But they did.”

“It was while Willard was with us that we received a phone call from my sister, Gertrude Nipper, during the night of the 2nd of December, 1930 telling us to drive immediately to the hospital where our dad was seriously ill after surgery.”

“We had a model T Ford roadster with side curtains but we did not have enough gasoline to drive to Eldora. Consequently, we were delayed reaching Eldora because of our difficulty in finding a filling station that was open at that time of night. When we did reach the hospital Dad was dead. Life was never the same for any of us.”

“Willard finished his year at Cedar Falls, then went home and got a temporary job with a construction company. Kenny had been helping Nip with well drilling so he had a little money. Also our mother had some money dribbling in from wells that had previously been drilled. Vivian was in nurses training at Marshalltown and at the time of Dad’s death she had one and onehalf years left before graduation. She said I made her uniforms which I don’t remember, and sent her $2.00 a week during that time. So, for about a year after Dad s death things with the Hartmans were not very good but were tolerable.”

“Then the depression really struck us. The tenant on the farm could not pay the rent so Ma could not pay the taxes on the farm. The Nippers gradually phased Ma out of the well drilling business and eventually took the equipment (without remuneration) and the jobs, so Ma’s little income from that source came to an end; ditto Willard’s construction job. Viv was graduated in the spring of 1932 but could find no work. Deere’s plant shut down and John was out of work. I was earning $15.00 per week in the law offices of Reed and Beers.”

“Mr. Mossman had been a tenant on the farm for several years but had not paid any rent for a total of three years. In about 1932, some of the area farmers had gotten together to work out means whereby tenant farmers could remain on the farms and whereby both the tenant and landlord would derive some benefit from the arrangement. In the Hartmans’ case, Mr. Mossman agreed, that if we permitted him to remain on the farm, he would do certain things including giving us a fifty-fifty split on the spring pigs.”

“Early in the spring of 1933 Willard and Ma came to Waterloo to “talk business” with John and me. Tena wanted to move the family back to the farm where they could at least raise some food. They would have the spring pigs from Mr. Mossman. Willard had lists and figures and computations. We sat at the dining room table while he proved to us that they could make a living on the farm. He explained what they would need to get started. John and I knew absolutely nothing about farming. Of course neither did Willard but we lost track of that fact because he was so confident, enthusiastic and persuasive. He soon had us sold. They needed a loan in an amount of around $300 as I remember it, and they got it. I don’t know where in the world we found the money; maybe the banks had reopened by that time or we may have borrowed It against our Savings and Loan account, I just don’t remember (The Farmers Savings Bank in Steamboat Rock never closed during the depression). Several years later Willard and Olga paid the note. We were to learn later, the hard way, that Willard’s figures did not include anything for repairs, maintenance and replacements.”

“The family moved to the farm in March, 1933. Willard had purchased used equipment (not the riding kind either) and two horses, one of which was blind. The Nippers got real generous and gave them 50 chicks and Agnes gave them 100 chicks which she bought with the money she had earned the summer before with her popcorn machine. Mr. Mossman did not keep his agreement to give Ma half the spring pigs; he said her half died. The loss of these pigs was a major catastrophe.”

“The family had no income, not even for groceries. I was able to send them $3.50 a week. I was the only person in our group that was working and I had already assumed some obligations which had to be paid.”

“We lived in John’s sister’s house on Logan Avenue, and had agreed, as our rent, to make the monthly payments to the Savings & Loan. After John was out of work we could not pay that much and the Savings & Loan told us that if we could pay the interest every month they would not foreclose. This we were able to do.”

“We had some friends, Minnie and Roger Ellis, who were having troubles. Rog worked for the Prudential Insurance Co. collecting weekly and monthly premiums on life insurance policies. The Company said he had used about $35 or $40 of their money for his own purposes. I ‘spose he probably had. It would have been easy to reach into all that change and use a quarter now and then. It would have bought two dozen eggs and a loaf of bread. Roger was absolutely honest, just a victim of the times. Anyway, the Company wanted its money or else … so Rog and Minnie gave up their little apartment and moved into our spare bedroom, and were with us about a month or so. Some relatives in Chicago took care of the Prudential matter and eventually the Ellises went to live with them. Then there were only the two of us to feed.”

“We had other friends that needed help too. The Schwerins won a coal stoker for their furnace In some lottery deal. We had a stoker and it was our greatest convenience, so we were happy for our friends’ good luck. But there was a catch. It would cost $20 to have the stoker installed. No one, and I do mean no one, had $20. Since I was the one earning a regular weekly salary, John and I agreed to pay the $20 in installments. So, when the family moved to the farm we were able to send them only $3.50 a week. Incidentally, the Schwerins repaid the $20.”

“The $3.50 per week wasn’t much money but it was regular and we could count on it. The family spent the money very judiciously. I marvel at all they accomplished with it. They allocated a certain amount for Willard’s tobacco, something for gasoline so they could get to town, and the rest went for groceries.”

“I have two memories that stand out above all others. In a manner of speaking, they still haunt me. One is the picture of broken hearted Willard carrying his dead pet dog in his arms.”

“The other of Ma and Willard when they returned from seeing Attorney Ryan in Eldora about securing some compensation from Mossman. Mr. Ryan could do nothing for them because he knew that Mossman had no money or other property and a judgment against him would be uncollectable. Ma wasn’t in any position to insist as she couldn’t pay the attorney’s fee.”

“John and I were at the farm when they returned. It was a miserable day, hot and windy. Tena was wearing a black straw hat jammed down over her forehead, her hair stringing out from under the brim. Tears were streaming down her cheeks; she was hot, tired, frustrated and discouraged.”

“Willard put his arm around her shoulders but John and I just stood there helpless. We were too young and inexperienced to have any practical Ideas; we didn’t know how to help her or comfort her.”

“There was a certain air of hopelessness here. We looked to Mother for answers she did not have; and she had no one on whom to depend, no one to whom she could go for advice. We missed Dad. He had been so imaginative and innovative…he would have found a way out.”

“This was a very trying time for everyone, especially for Willard. He had never lived or worked on a farm and knew absolutely nothing about farming. Uncle Herman Gast, Mother’s brother, had farmed all his life and lived on a farm not too far from the Hartmans. He was wonderful to the family, helped get the crops planted and taught Willard all he could. He may even have furnished the seed the first year. If he didn’t I don t know where it came from. That first spring was a revelation. I remember Viv telling me that one day there was nothing visible but brown soil, and the next day there was a miracle … rows and rows of green sprouts.”

“John was a resident of Pennsylvania when he enlisted during World War I. That state declared a veterans’ bonus and John got $70 or maybe $90. He had needed a pair of pants for a long time so he purchased a pair for under $10.00 which left a beautiful nest egg. Then we got a letter from Willard.”

“One of the horses had died and they absolutely had to have two horses. He didn’t say how or why the horse died but later Me told us that Willard had been doing some cement work around the place and had rinsed the buckets and other equipment he had used, in the stock watering tank. One of the horses drank from the tank and died of hardening of the arteries plus. Poor Willard had a lot to learn. Remember, Willard was only 19 or 20 Years old.”

“In Sept., 1933 Viv got a job in the Eldora Hospital, assumed responsibility for the groceries. Every week on pay day she bought groceries for the following week for the folks on the farm. She always included tobacco and popcorn for Willard. Therefore, I no longer needed to send the $3.50 each week.”

“There was still very little cash coming in. Willard was dating Olga and during school breaks or maybe summer vacations, Viv would give Willard money for gasoline so be could drive to Clutier to do his courting. Everyone, men and women, wore hats. Willard did not have a-good hat so, for his first trip to Clutier Viv gave him money with Which to buy one.”

“Willard and Ma managed to get a cow or two or maybe three and Viv bought them a separator. Then they had some cream and eggs to sell. Also Ma was able to rent the house in Steamboat to the new coach (Kenneth Amsberry) and that helped too. By the time Viv married Don In the fall of 1934 the family was almost able to make it on their own.”

“Willard and Ma continued to live together on the farm from the time Viv married in the fall of 1934 until Olga moved there in the spring of 1937. Times were still very rugged and the daily frustrations almost unbearable. The winters were long and lonely for both of them. One winter in particular was bitterly cold and snow drifts were higher than the fences. There was a hard crust on the snow so the folks could walk to the neighboring houses over the fences and across the fields. This was an enjoyable interlude and relieved the dreadful monotony.”

“One Christmas Willard and Ma had no money for gifts but had lots of time. Ma busted herself making pot holders and taught Willard how to make them. So Ma and Willie made pot holders for gifts for the rest of the family.”

“On a certain winter evening Willard was sitting, chair tipped back his legs on the oven door (wood burning kitchen range), toasting his feet, eating popcorn and reading a wild west magazine. All at once he heard a loud, shrill scream close at hand. Willard was so startled he jumped and the chair, Willard, popcorn and magazine decorated the kitchen floor. When he realized it was merely the old “whistling” teakettle he was so angry he took the iron lid-lifter from the stove and began beating the old teakettle. I can just visualize this little episode and am laughing so hard I can hardly type. I have never said Willard didn’t have a temper, have I?”

“Willard was what I call a “fey” person He had many unexplained, supernatural type experiences. For instance, when he was planting his first corn crop he was unable to get it all done during the daylight hours so he worked in the dark. We could not understand how he could do this successfully. He told us that he simply followed the bright light that went ahead and guided him. In the morning it was noted that his “night” rows were just as straight as those he made during the day.”

“One fall he had to cut down a big tree, probably for fuel. It required a crosssaw, but Willard was alone with no human being to work the other end of the saw. However, he did cut the tree down with that cross-saw and said that when he pulled the saw through to his side, some power pulled the saw back to the other. Of course all this sounds a little far-out, but the tree did require a cross-saw, Willard was alone, the tree was felled.”

“One day he told us that he had just seen a young woman with reddish blond hair holding out her arms to him and beckoning. We thought immediately of his High School girl friend, Ruth Schwitters. However, he later, met and began dating Olga Kremenak Olga was a school teacher at Steamboat Rock, rooming with Mrs. Gellhorn. She was a young woman with reddish-blond hair. We like to believe that Willard’s vision was Olga.”

“There are other incidents of this nature but you probably wouldn’t believe them if I did include them.”

“It seems that every time Willard got into difficulties during those first years on the farm, some unknown power helped him. However, when he became more mature and knowledgeable and no longer required much help, he ceased to have these experiences.”

“In January, 1937 the mortgage of about $3,000 on the farm had to be renewed. The insurance company holding the mortgage refused to renew the loan to Tena because they felt she was too old. She was about 62. Therefore, in order to refinance and satisfy the requirements of the loan company, it was necessary for Tena to deed the place to Willard.”

“Willard and Olga were married in March, 1937 in the pastor’s study of the First Presbyterian Church in Waterloo. Edna Lewis, Kenneth’s future wife, was a beautician and gave Olga a complete beauty treatment including a manicure. I remember the manicure because I had never had one. Olga had a sweet pea corsage. John and I “stood up” with them. I remember that Olga cried before the ceremony.”

“Olga was still teaching in Steamboat at the time of her marriage. In those days married women were not allowed to teach school. Therefore, this marriage was to remain secret. We managed to keep the marriage license out of the Courier but I guess the news was just too good to keep because the two newlyweds announced it. Olga continued to teach the rest of the school year and to room at Mrs. Gellhorn’s during the week. She spent the weekends on the farm with Willard.”

“Olga moved onto the farm at the end of the school year. Her dad gave the couple one cow, one heifer, one calf for a wedding gift; and later when it was needed, a load of oats. Olga gradually assumed responsibility for the home and Tena was free to make extended visits to relatives.”

“When Ma deeded the farm to Willard it was not actually a sale but was done out of necessity. Later, he entered into a contract of some sort with Ma and became the actual owner of the farm. On Sept. 19, 1939 Ma married Fred Meckstroth and moved into his home at Garner, Iowa.”

“Mother had been a widow for seven years when she married Fred. Fred had been married to mother’s cousins Lydia Gast Stille (of the Wm. Gast clan), who had been married previously and had four or five Stille children. My mother and dad used to visit the Meckstroth family at least once a year, Both Fred and Mother knew each other over a long period of time. Fred raised the Stille kids; they were adults when Lydia died, and Fred remained a widower for several years. I think Martha Gast Prull Jenssen, Lydia’s sisters was responsible for getting Fred and my mother together. They lived in Garner and I’m sure neither Fred nor my mother could have been happier. They were a great deal alike except that my mother was a great kidder and practical joker and Fred was not accustomed to that.”

“As Willard got older he did exaggerate a little to make his conversation more interesting, and he liked a good argument. Over the years Olga and Willard had many family dinners. One of Willie’s little tricks was to introduce a controversial subject at the dinner table and then ‘ sit back and listen to the others go at it tooth and nail. Sometimes the arguments became very heated. Russ Holmes has something to say about this trait of Willard’s: ‘It used to amuse me when I ran the drug store , when Willard would come in and look over the people that were in the store. If most of them were Democrats he would start giving the Democrats the dickens, but if they were mostly Republicans he would point out what was wrong with the GOP. He could do such a good job of it that whoever he was talking to would think he belonged to the other party.”

“William Morris Hartman was born December. 4, 1940. Like all new Parents, Willie and Olga thought their child was super. (Time proved they were correct.) I was out to the farm when Bill was just a few months old. Willard put Bill on his stomach and showed me how the baby could Inch along on his belly… this was much advanced for an infant his size, according to Willard.”

“Well, every owl thinks Its owlet has the biggest eyes!”

Over the years Willard and Olga slaved to Improve the farm and Make a good home and they succeeded. Maybe they worked too hard … Willard died of a heart ailment on February 17, 1972. Those of us who are still around know what the Harman’s’ present situation Is, but for those who may read this In the future I will say only that Olga, as of this date, December 1, 1981 continues to reside alone in the house on the farm; that William, who lives in Iowa Falls, farms the land.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, was elected president in the fall of 1932. When he came into office he declared a national emergency and began putting into action a number of programs to end the closing of banks and foreclosure of farms and businesses. Thousands upon thousands of people were without jobs. Various government programs were initiated to provide jobs for those who could find one nowhere else. The Works Progress Administration W.P.A., the Civilian Conservation Corps; C.C.C.

The old iron bridge was replaced in 1936.

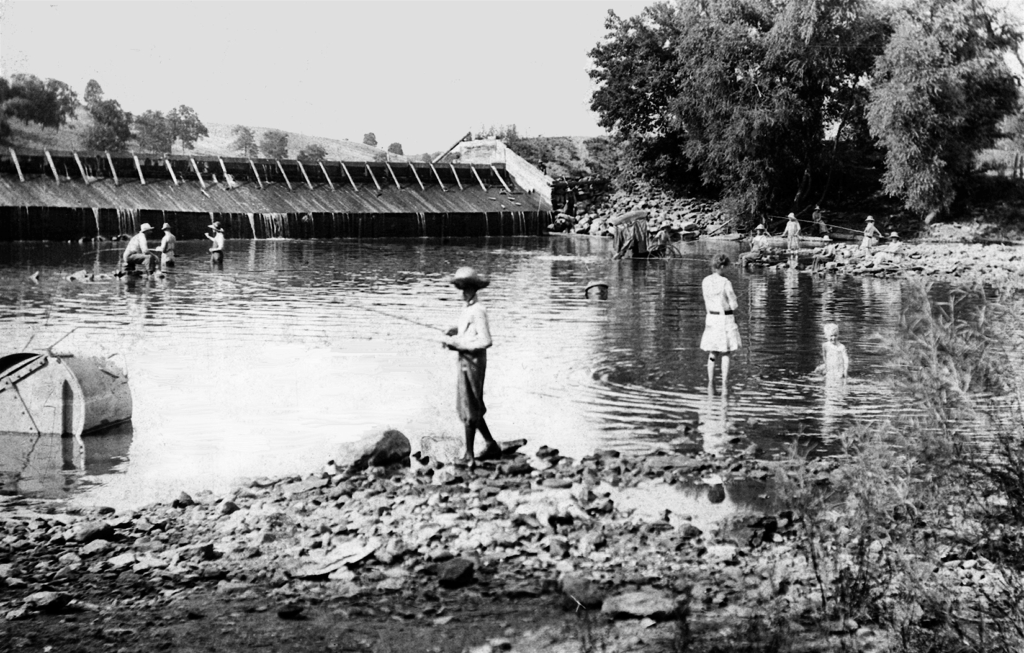

Last look at the old wooden dam

Additional views of the wooden dam.

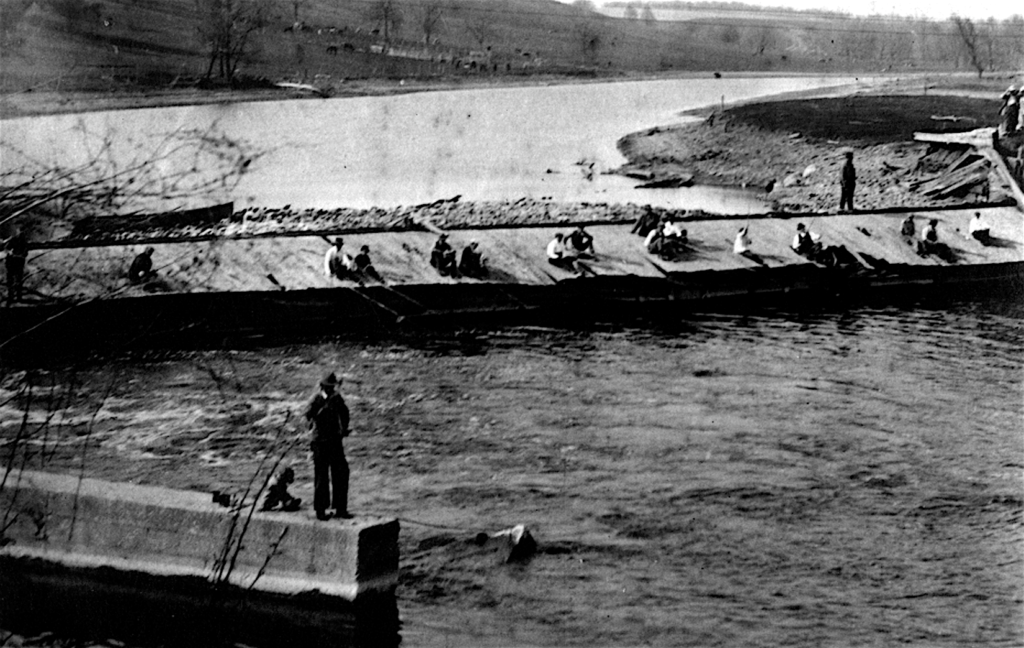

View of the river after the wooden dam was washed out.

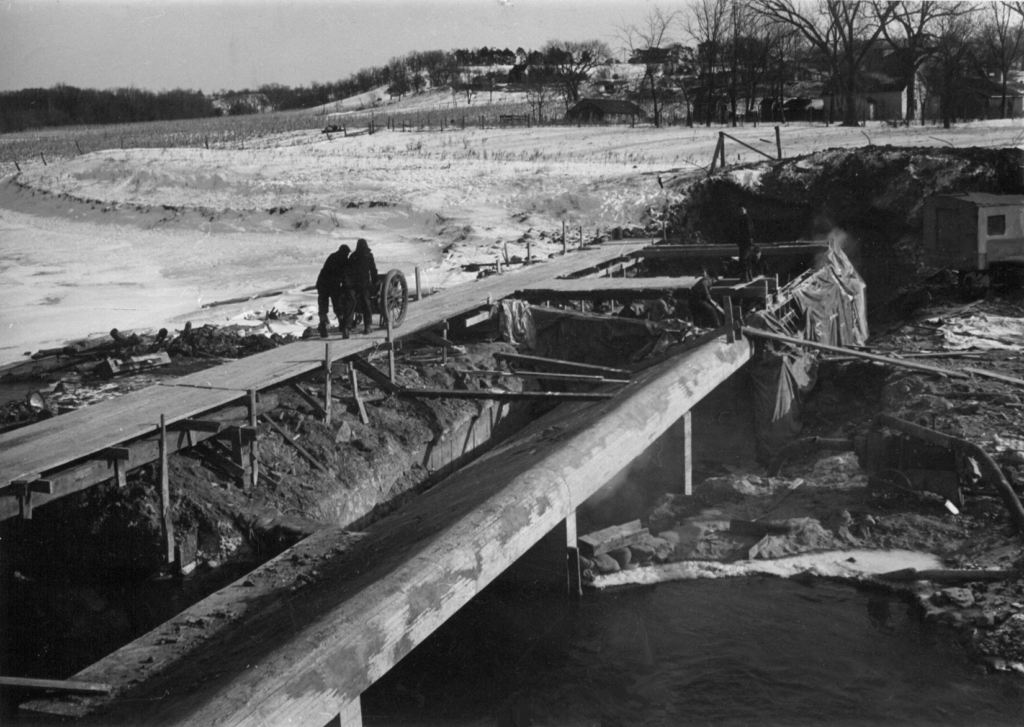

Construction of the new concrete dam.

The completed dam. The building in the top and right photos is the short lived power house.

The old iron bridge on the Iowa River served Steamboat Rock until 1936, when Weldon Brothers of Iowa Falls, constructed a cement bridge. It was a WPA project and cost $23,980.

The W.P.A. built the dam in Steamboat Rock, and helped put in the city water system. The C.C.C. built the parks and paths in the area including a great deal of work at Pine Lake. The stone used in that project was the last taken from the quarries southeast of Steamboat.

Back to the depression and farming, Rex Folkerts, endured the difficult depression years on the farm, due for the most part to drought and very poor farm prices, not because of lack of hard work or ability. He was willing to try new methods of farming as well as new crops. Early in the 1900’s a new industry, that of raising sugar beets, was started in the area around Steamboat Rock. Rex, was one of the farmers who raised beets. He raised beets for about five years, but stopped when he found that they took so much out of the soil. In the 1930’s, farm prices were very low, and to make matters worse, drought hit in 1933, and Rex had no harvest that year, in ‘35, it was nearly as bad. His son Harry Folkerts was a young boy and kept the family in fresh game. Harry went rabbit and pheasant hunting every day to put meat on the family table.

There was no escape from the heat of the summer of ‘35 and ‘36 as there is today with our modern air conditioning. Back then people spread blankets out on the lawn hoping to get a little breeze and possibly some sleep.

As if the Depression, heat and drought wasn’t enough, grasshoppers and cinch bugs destroyed corn, wheat and oat fields. Cinch bugs crossed the highways and as cars drove over them the surface became just as if they were ice covered. Farmers didn’t have enough feed to feed their livestock, and if they lived, they lived near starvation.

In mid September the heat wave broke and the rains began to arrive.

The summers were hot and dry and the winters were equally cold and snowy. The winter of 1935/1936 was very severe. There was a lot of snow and it was bitterly cold. Roads were blocked for days on end and using the automobile, if they had one, was out of the question. There was a 90 day stretch that not one car came into town. The only way many farmers could go into town was by bobsled and horses, cutting fences and cutting across fields. By mid-January all the roads were still closed. Glen Miller of Eldora operated the county snow plow. The road from Eldora to Steamboat (this was the river road) had been opened. Around 35 men from Steamboat went with Miller’s plow to open the road east of town. Glen would take a 50 yard run at the snow and go until the plow was buried and then the men would dig him out. He would back up and take another run at it and they would dig him out again, and so the routine went. They finally got just east of the county line about 4:00 and the men were tired out. They got the plow turned around and headed back to town. That night a big wind came in from the northeast and by morning the road they had worked on all day was blocked with snow again.

Later in March, the county purchased a nose plow to be mounted on the front of a 90 horse power caterpillar tractor. In addition the plow had six foot wing plows on each side. The new plow was sent out to clear the same road the old plow and the 35 men had cleared earlier that winter. Even with this plows size and power it took a full day to reach the county line.

© 2020 Steamboat Rock Historical Society | All Rights Reserved

Powered by Hawth Productions, LLC