SRHS

Steamboat Rock Historical Society

THE WORLD GOES TO WAR ONCE AGAIN!

A FIRST HAND ACCOUNT

There were many from Steamboat Rock that answered the call to serve their country. My father-in-law, Hollis Havens was in the Navy prior to the start of the war. He and his wife Meta Mae recalled many memories of the war years.

Hollis’ story began two years prior to the beginning of the war.

”We’ll start with the winter of 1939. We were living in San Diego up on the hill at 14th and A Street in an apartment complex called High Courts. I was stationed on the light cruiser USS Memphis, and from on the top of the hill where we lived, you could see the Memphis and the rest of Cruiser Division 6 moored out in the harbor.”

Hollis L. Havens

“I didn’t come home one afternoon at the usual time of 4:00 p.m., or 1600 hours, as the Navy would put it. Anyone watching the bay at that time would have noted Cruiser Division 6 steaming out to sea under a full head of steam. Incidentally, Cruiser Division 6 consisted of the Memphis, Milwaukee, and the Marblehead.”

“The dependents ashore didn’t know what was transpiring, but we were aware that a strange underwater craft of unknown origin had been sighted by a patrol craft off the coast. We cruised all night and until the next day, but didn’t see anything. It was quite exciting, but nothing like what would happen a few years hence.”

“The war in Europe and the Atlantic had been going on for some time, but for the most part, the West Coast was quite peaceful. The aircraft factories and shipyards were making some progress but other than that, the war in Europe seemed a long way away.”

“On May 5, 1940, I was discharged from the Navy at Norfolk, Virginia after Cruiser Division 6 had been moved to the East Coast for temporary duty with Commander Air Scouting Force, Com-AirSco-For for short.”

“I took the train back home, Steamboat Rock, Iowa, and after a few days rest and relaxation, I applied and got a job with the Woodward Governor Company at Rockford, Illinois. That didn’t last too long. The draft law went through in June, and I was informed that all men with any kind of military experience would be drafted in the Army. I couldn’t see that, so I quit my job, went to Des Moines, and said, ‘Get me back in the Navy, quick!’”

“I received orders back to the Navy receiving station in San Diego. The receiving station was known as the McCardless Navy. It was run by Captain McCardless, and he was a tough old biddy.”

“I worked on Old World War I destroyers while waiting for assignment to a new duty station. These old tin cans were being refitted and sent to England for convoy duty. As fast as we could turn one of them out a British crew would take them over. What a bunch of rust buckets. They served a good purpose, though, and did a good job in the war effort.”

“During this stay in San Diego, we lived in a real neat little house on Florida Street. Verna (Meta Mae’s sister) was with us and after about a month, I got orders to the USS Medusa at Pearl Harbor. And so Meta Mae and Verna went back to Steamboat Rock, and I boarded the Battleship Idaho for Pearl.”

“Aboard the Medusa I was assigned to the motor rewind shop. Just like a civilian job–worked eight hours and that was it.”

In November, the Medusa was scheduled for overhaul in the Bremmerton Naval shipyard at Bremmerton, Washington. So back to the states. We stayed in Long Beach for about a month before proceeding to Bremmerton. Meta Mae and Louise Harms (Cousin, later Louise Aikes), came out, and we lived in a small house in Wilmington. We had an oil well right in our back yard. That didn’t go with the house, though!”

“Meta Mae, Louise and a friend off the ship and I drove our car to Bremmerton, and we got a place to live, finally, out on the Hood Canal. It was a summer home, and we didn’t know that when the tide came in, our house would be surrounded by water. Anyhow, we had a wood stove for heating, and I bought a pile of wood and then stacked it along side the house. The tide came in and there went my wood pile, floating out to sea. I managed to rescue some of it and piled it on the back porch. This wasn’t a real good place to live in the winter. But, I being a rather backwoods farm boy from Iowa, thought it was great! The wild ducks used to swim quite close to the porch, and one day I thought it would be good to have duck for Christmas. I made a bow and arrow. The arrow had a big fish hook on the end that I had straightened out, then a long string on the arrow to retrieve the duck. Anyhow, the ducks didn’t exactly like the commotion I was making out on the porch, and they seemed to sense the range of my crude weapon. They moved just beyond range. I gave the arrow a little extra flip, pulled it back too far, and the fish hook went right through my thumb and pinned it right to the bow. There I was. I cut the string on the bow and then reached in between the bow and my thumb and cut the fish hook with a pair of diagonal pliers. I went out and bought a chicken for Christmas.”

“After the first of January 1941, Meta Mae and Louise drove back to San Diego and took the train from there back to Steamboat Rock and me on the Medusa, back to Pearl Harbor.”

“We tied up to 10-10 Dock next to the Battleship Pennsylvania alongside for overhaul. This was a good location. After hours we could go ashore without having to ride a liberty boat. Great life — beautiful tropical atmosphere, swimming and playing golf. That wouldn’t last too long, though, although we weren’t aware of it at the time. Things were pretty quiet.”

“The next April, I was ordered to mine warfare school in Yorktown, Virginia. This came in quite well because Larry (first son), was to come along about this time. I caught a transport back to Long Beach, and then took a bus to San Diego to pick up my car. I drove nonstop to Steamboat Rock. Larry didn’t quite make it before I had to go on to Yorktown. He did make it on April 21, and 17 days later Meta Mae and Larry came out to Virginia.”

“I had rented what they called a cabin camp. It had two rooms. So we made a bedroom out of one room and the other a living room and kitchen. I bought a little washing machine. The bathing and toilet facilities were in the oil station. It was summertime, so we all sort of camped out.”

Meta Mae recalled, “The grass came up through the floor, particularly under the bed. The mosquitoes were ban. The cabin had a bed, table, and one chair. We made a cupboard from an orange crate. We had to carry water from the gas station in dish pans, heat it up, and put it in a handcranked washer-wringer. We would fill up the washer in the morning to do the baby wash. A sailor from Steamboat was there, so we asked him over for dinner. We gave him the chair, so Hollis sat on a suitcase and I sat on a box. No one complained; We were happy with it. Every afternoon it stormed. I would stand in the middle of the room with the baby and wait ‘till it was over. There were few medical doctors there. To weigh the baby, I went to the general store and put him on the scale. You couldn’t drink the water so I drank Grapette. The water was so bad.”

Hollis continued, “There were ten units, and they were all occupied by the students at the school. The class graduated the first of July and everyone headed out: The women back home and the men back to their ships. We drove back to Steamboat Rock, and I was to leave right away for the coast–the Union Pacific to ‘Frisco, and so back to Pearl Harbor by transport, and the Medusa. Back in the same routine again. And so went the summer of 1941. Everything still quiet and peaceful.”

“I had my time in to be eligible for Chief, but I didn’t have Gyro Compass School in my record, so I got orders for the January 1 class.”

“In the meantime, the Medusa left 10-10 Dock and was now moored behind Ford Island, aft of the old Battleship Utah. That was a long ride to the beach, but every Sunday morning all summer, three other shipmates and I would go swimming at the YMCA pool. We would go at 6:00 a.m. and come back on the 8:00 boat from the fleet landing. That was the time and place where the Japs machine gunned the landing and killed a number of sailors, on Sunday morning, the 7th of December, only the four of us weren’t there that morning. I had transferred off the Medusa to the transport USS Henderson on Saturday afternoon to go back to the states, and I never did know why the others didn’t go swimming that morning.”

“After getting orders to school I had a backlog of work I had started, so I did a little overtime to get everything done before I left. I had been working on rewinding a 200 horse armature from a deck winch on the battleship Arizona, and I finished on Friday afternoon and delivered it to the Arizona on Saturday morning. The armature never got installed. It’s probably still sitting on deck under a few feet of water.”

“Anyhow, Saturday afternoon, I went aboard the Henderson and about 5:00 p.m., we went out through the antisubmarine nets and put to sea at a full 9 knots–really a speedboat! At 7:55 the next morning, we were about 60 miles out of Pearl at Mokapu Point, Kaneohe Bay, still within sight of land when the Japs hit Pearl.”

“That was a real shocker. Reports kept coming in all day. Also, they reported 3 two-man submarines captured, and it’s very likely when they opened the nets for us to go out on Saturday, those little sneakers came in. That channel is quite deep and they could have.”

“We kept on going for the States, and that night we saw two burning freighters, but we didn’t stop. We had women and children on board and couldn’t take a chance. In fact, we had one more baby on board when we got to ‘Frisco than what we had started with.”

“We kept grinding away with our knee-action turbines and finally, after eleven days, the Fairlan Islands loomed up about 9:00 at night, so we had about 50 miles to go.”

“We pulled into the bay and docked at Yerba Beuna Islands, better known as ‘Goat Hill.’ That’s the receiving station for Navy personnel. It’s right in the middle of the Bay Bridge and connects with the manmade Treasure Island, the home of the 1939 World’s Fair.”

“I sent a telegram home that night and after eleven days, they knew I was o.k. and where I was. I guess that was quite a relief.”

Needless to say, word reached Steamboat Rock, of the bombing of Pearl Harbor the morning it happened. Concern for Hollis, was compounded by the fact that those at home were not aware of his leaving the Islands the day prior to the bombing.

Meta Mae recalled that morning in December and in the days to come. “Well, I was in Steamboat Rock at my home, living with my mother and sister, and we were getting Sunday dinner as Hollis’ folks were coming for Sunday dinner that day.”

“It was about 11:00 when it came over the radio that Pearl Harbor had been bombed. I can still hear President Roosevelt’s message to the nation that ‘this day will live in infamy with the bombing of Pearl Harbor.”

“With the realization that my husband was aboard the USS Medusa at Pearl Harbor, time seemed to all at once come to a screeching halt.”

“Well, it was a little hard to believe, and we kept hearing the reports and knowing that it was true and everyone was upset about it. We kept listening to reports, and I carried my little radio with me everywhere I went and even took it to bed with me.”

“The slowing of time went on for the next 11 days then late in the evening on December 18th, a telegram arrived indicating Hollis had arrived in San Francisco aboard the USS Henderson and was very little the worse for wear. We were so glad to get that telegram. What a relief for this family, but for the families of some 2,000 or more other Navy men, it was a different story; those lost in Pearl Harbor.”

Hollis continued his story with the day following his arrival back in the States. “The next night, I went to San Francisco and got a hotel room and about 9:00, placed a telephone call home and went to bed. At 2:30 a.m., the call came through. We were only allowed 3 minutes, so it was a short conversation on both ends of the wire.”

“The next day, I boarded a train for San Diego and to gyro school.”

Meta recalled that three days later on Monday evening Hollis called again from San Deigo. “He said he was going to Gyro school and wanted to know if Larry and I would come out.”

Hollis went on, “I had a rather hard time finding a place to live. We now had one young one in the family, and landlords just would rather not rent to families with children.”

“Finally got an apartment on El Cajon and 59th Street. Upstairs apartment, but that’s fine.”

Meta Mae packed and went to Marshalltown to take the train. She boarded the Great Western there and in Kansas City changed to the Santa Fe to San Diego. Meta recalled, “There were other Navy wives on the train. They were going out to the coast too.”

Hollis went on, “Meta Mae and Larry came out on the train, and we set up temporary housekeeping. I bought an old 1928 Chevy 4-door for $25.00. The back door wouldn’t stay shut so I tied a rope across them. We didn’t need the back seat anyway. Had a few flat tires during the next three months, but when you’re young, what the heck!”

When Meta got to San Diego, she remembered that they had a small budget to work with. “There were an awful lot of people in San Diego looking for housing. Hollis was making $67.00 a month, rent was $25.00, and train fare was $37.00 round trip. He ate his meals on the ship, and I didn’t eat much, so it worked out.”

Of their apartment she recalled, “It was very satisfactory for a short stay in Diego.”

“During the next 3 months several events took place like city blocks organizing. Every block had a block captain and he would keep everyone informed on blackout requirements and in the event of blackout, he would inspect dwellings in case of a complete blackout. We had occasional drills and a couple of times, the real thing happened. One night after the sirens blew, almost immediately there was a knock on the door. These men came marching in and went over to the little heater and put out the pilot light. I had forgotten all about it. There were shelters on the streets and in black paint and big letters were marked ‘SHELTER’. After the war, you couldn’t buy denim because they had used it all up for blackout curtains.”

There were good times that Meta also recalled, “The Lou Luiken family came out to visit their son Carl (in the Army), who was stationed in San Pedro. They stayed with us for a couple of days. We showed them around the area and entertained them the best we could under the circumstances.”

“On occasion when Hollis had the duty, I would go to the training station to see a show. The USO shows were getting organized and on one occasion, Bob Hope and Betty Hutton entertained.”

“The defense effort was now in high gear. The naval training center was building up. Temporary buildings were going up. The aircraft factories in San Diego were going full speed ahead.”

Hollis added, “The defense efforts were really in high gear now. I really was amazed what progress had been made in such a short time. The aircraft factories were buzzing; blackout regulations were in effect. Recruits were pouring in from all directions to the Naval Training Center and the Marine Base. Some of the new military training centers looked a little temporary, but it’s hard to believe that so much progress was being made. The factory areas were all camouflaged with nets and colors that just blended into the surrounding area.”

“We may have lost a lot of lives and material items in the Pearl Harbor disaster, but I have always believed that was the biggest mistake the Japs made during the whole war. It created a spirit of cooperation in this country. I believe it shortened the war by at least 2 years, and that, in itself, saved a lot more lives than those lost Pearl Harbor.”

“The next couple of months a number of events occurred, like the Army firing 1800 rounds of antiaircraft ammo over Los Angeles one night. They never did know what they were shooting at. Then at gyro school, they issued each one of us a 1903 Springfield rifle and a bandoleer of ammo. They gave us a big, old stake truck for a transport. Our school head instructor was a Lt. Commander, and he was in charge of our brigade. He was about as much of a field commander as a turkey gobbler. He got up before this nondescript group and made a speech. He said, ‘We are a hardhitting, fast-moving, mobile unit.’ Everyone sort of snickered. He was a reserve and his military experience a little bit on the brief side, and being a combat field commander wasn’t exactly his specialty. No sarcasm intended. The reserves did a very good job, and most of them were specialists in their line of work.”

“School ended in April–Meta Mae and Larry went back to Steamboat Rock and I went back to Pearl Harbor.”

When Meta Mae and Larry returned to Steamboat Rock, she recalled, “It took 3 days and 2 nights to make the train trip back to Steamboat Rock, and it cost $35.00 for the ticket, and when I got back to Steamboat. I got myself involved in the war effort by working on the draft board, planting a victory garden, and going around town with Larry in the Taylor Tot, selling war bonds.”

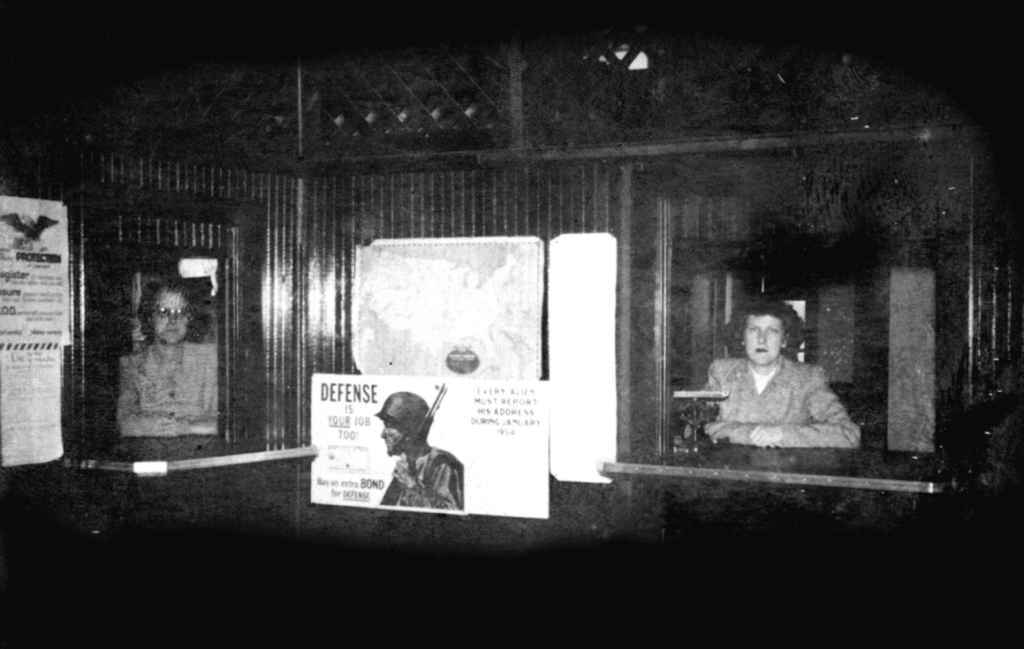

Marie and Ruth Eilers in the Post Office in Steamboat Rock. This Picture was taken during the war. A savings bond poster is displayed on the wall between the windows.

“They had a registration office down in the town hall. I helped register the fellows. It was because I could type.”

“Everyone had big gardens; they called them Victory Gardens, and they would can everything they could get.”

“Scrap iron was a very valuable commodity those days and we had regular scrap iron drives. We collected every bit of metal we could, everything from soup to nuts. We made a regular event out of this and the whole town pitched in.”

“Another thing comes to mind and that’s the candy bars. They were made of soy beans and they weren’t really very good. The other oil products that normally went into candy like butter was used for the war effort.”

“And, of course, the rationing of most all commodities. We had ration books. That was for food, especially for the coffee, sugar and flour. We really never were without anything; we had enough, but we had to be careful. Flour and sugar came in cloth sacks that were in a print material so we could make dresses out of the sacks. There wasn’t a thing wasted.”

“We did use sugar substitutes as rock candy that came in a shoe box. The flour wasn’t good; you couldn’t bake with it. It was a funny color and consistency. I got good flour from the ship’s commissary when I was on the coast. Coffee was chicory. It took about 3 years after the war for supplies to normalize. You didn’t hoard food; it was considered immoral.”

“Gas rationing was on. We didn’t use cars anymore than necessary, and we always would walk wherever we could. If you needed something, machinery, parts, tires, you had to have a written order and be authorized to buy it. There was a ration board in Eldora. Tires were hard to get and you had to turn in your old tires.”

Harold Luiken, who owned the local Chevrolet dealership in Steamboat Rock when the war broke out, soon found that automobiles were going to be in short supply for the duration. This meant that he was in need for an alternate means of support. He was contemplating a factory job in Des Moines, when he received a call from Mr. Ed Lundy of Eldora.

The following is a quote from Harold’s book, My Three Score and Ten…Plus…, “The war rationing program was just getting started and the rationing board was looking for a chief executive officer to manage the rationing office. Mr. Lundy was the board chairman. He had heard I was looking for a job.”

“The Rationing office was in Eldora and this of course made the job more appealing than the others since I could be home with my family every night. My army draft classification was such that I would not be drafted for some time at least because of my family. (Harold was 32 years old, married and had two small boys). The position required a civil service examination. To make matters worse, all World War One veterans had a preference rating for this position. When the time came for this examination, three men were on hand for the exam. One was a veteran and seemed a cinch to get the job. To my amazement, when the reports came back, Harold H. Luiken had been selected for the job.”

“On September 1st, 1942, I began the work of managing the Hardin County Rationing Office. What a job this developed to be. We were rationing gas, fuel oil, tires, sugar, meat, and anything made of rubber, such as hip boots, etc. Later came the price control program and we had that to administer also. Mr. Lundy was a great help to all of us. It was an entirely new experience for all of us. We were serving 22,000 residents of Hardin County. Seven ladies were employed, Bernice Nissen, Beulah Burgess, Alice Fourby, Jean Oldham, Doris Ruppelt, Jean Folkerts, and Lydia Stickler.”

“As I said, it was a whole new program and no one ever had worked with this kind of program, even the people who made up the rules were inexperienced. To give you an example of the rules, a gentleman in Hardin County had received a phone call telling him that his mother had died in Missouri. He was a farmer operating on a gas ration for farm services only. He came to see if he could be given an additional amount of coupons to drive to Missouri to arrange his mother’s funeral. In the rules I found where it stated that no special ration could be made to attend funerals. I simply told this man to go to Missouri and when he ran short of gas, we would figure out some reason for issuing him a supplemental ration of coupons.”

“The whole program was a farce in many respects.”

“Lawyers in Chicago and Washington were writing the rules covering the rationing program and it seemed to us that they had little knowledge of the problems we had in the farming community trying to operate within these rules.”

“We adopted a philosophy that the rationing laws would keep the people from acquiring all the various commodities covered by the program. Our obligation was to see that they did indeed get their fair share of all these goods. Every county was given a quota of all commodities according to population. We made a sincere effort to dispense the entire quota of all commodities every month. We believed this was our peoples fair share. If we had trouble staying within a quota, we would call the state office by the 25th of the month and request additional quota. Almost without exception, this request was granted. As we progressed and the people became acquainted with our plan, everything moved along quite nicely.”

Harold, did and outstanding job , and served in the rationing office for just over two years, from September 1, 1942 to December 30, 1944.

Meta Mae continued her story saying that, “Everyone, the different societies and organizations, were doing things for the men in the service, and they were sending cookies and candy and food and little gifts and little things they knew the servicemen could use. Some of the women were knitting sweaters for the servicemen, army green for those in the Army and white for those in the Navy. I didn’t know how to knit, and Lucy Greeves made Hollis a white sweater vest, but it was too big, so I took it apart and somehow made it smaller. I think that’s when I learned to knit. The churches were always having coffees and lunches for the soldiers. There was much done for the remembrance of the servicemen through the churches. They were always remembered at every service and prayer.”

“In 1942, women had a class; a nurse from the hospital taught us first aid. We ha d to learn to make hospital beds. It was held over the bank. Why we had to make beds, we didn’t know. Maybe they didn’t know how long the war was going to go on.”

“I wrote to Hollis every night and when I got mail back, it was always a whole hand full as mail went from the ship whenever they got into port or some other ship would pick it up. V Mail was the really fast way to send a letter. The letter you wrote on this form that was provided by the post office was shrunk down to a 35 mm film and sent overseas. At the base somewhere near your ship or station, the letter was re-enlarged and sent to you. All mail was censored”

“I don’t think there was ever a time in the history of this country when so many people worked so well for the good of everyone concerned.”

Hollis, in the meantime had returned to Pearl Harbor for duty on the Medusa. When he arrived, he recalled, “What a mess. The clean up had hardly begun. Most of the working facilities were back in order, but old Battleship Row lay there as a sad reminder of what can happen in a very short time when you let your guard down,”

“On the Medusa, around-the-clock working schedules had now been set up with eight hours on and eight hours off. That way we rotated, not getting the same shift all the time. I was in charge of one shift working on battle-damaged ships that came alongside. That put an end to swimming, playing golf, etc.”

“I took the test for Chief Electrician’s Mate and got it on August 1. This meant back to the States for a new ship. Ships were now being turned out so fast they couldn’t assemble crews fast enough. From the receiving station in San Francisco, I was first assigned to the destroyer, Abner Reed #525.”

“I really didn’t want any part of a tin can, so I talked my way out of that one and on to a submarine rescue vessel, the USS Coucal A.S.R. #8. Incidentally the Abner Reed, about six months later, went on duty off the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, ran into a storm with her fuel tank empty, and no ballast. She capsized and sank and lost a big percentage of the crew. I never was able to find out the exact number. Lucky again, huh!”

“The Coucal was under construction at Moore dry dock in Oakland. Part of the crew was assembled, but about all we had at this point was a hull with a roof on it. I had the job of inspecting the installation of all electrical equipment and wiring on 5 of this type of ship. I didn’t have much spare time. We didn’t have living facilities at the ship yard, so I rented a room in a private home in East Oakland. I ate all my meals in a restaurant and went back and forth to work on a street car. The ship yard was quite a place. I would say about half the workers were women, or I should say girls, between the ages of 18 and 25. A few were older ladies, but not many. They probably had their families grown up and gone and probably in the armed forces. They were a hard working bunch.”

“The Coucal was diesel electric drive. Really a beauty to operate. Good equipment and well-installed.”

“This, now, was the fall of 1942, and on November 22, along came Charlotte (daughter), and I wasn’t to see her until 19 months later when I cane back to the continental U.S. in 1944.”

“After commissioning the ship in December 1942, we picked up a concrete oil barge with 20,000 barrels of aviation fuel and diesel oil. With that in tow, we got on the great southeastern circle route and headed for Espiritoes Santoes, down past Christmas, Fanning, and Palmira Islands. It took us 42 days. And it was a good thing we had fuel on the barge. So, we took on fuel and continued on at our top speed of 6 knots. Only had one sub contact on the whole trip. We cut the tow loose and went after him. We dropped a lot of depth charges (ash cans) on him, but never knew what happened; no oil slick, and so it’s hard to tell.”

“I caught a 62 lb. tuna one afternoon. The skipper had to stop the ship so we could haul him aboard. All hands had fresh fish that night. By this time our fresh supplies were about all gone.”

“We arrived in Espiritoes on our 42nd day and not too much worse for wear. We were sure a bunch of brown-skinned sailors. On the equator and below, it gets pretty hot in January and February.”

“We dropped our tow and headed for Brisbane, Australia via Aukland, New Zealand. We took on a few Jap prisoners at Espiritoes for transport to Australia. We had them dogged down in an aft compartment. One of them got nasty back there, so we put him in the chain locker, way up forward; gave him some water and K rations and shut the hatch on him. That night we got into a really bad storm. We dove through a big wave, and it warped the hatch on the chain locker. The next morning we took out a well soaked corpse. We wasted the K rations. We probably would have shot him before we got him to Brisbane anyway.”

“After a one-day stopover in Aukland, we proceeded on to Brisbane where we took on food and fuel and headed north for the war front.”

“For the next year, we operated with Sub Ron 8 for Task Force 72. We did every kind of job you could think of, from pulling LSTs off the beach, shore bombardment, salvaging an ammunition ship off the Great Barrier Reef, to chasing enemy subs’ antiaircraft cover. You name it, we did it.”

“We were pretty lucky, though; we weren’t big enough for the enemy to pay much attention to. As long as there were bigger ships around, they left us alone. Our draft was shallow, the Jap subs would fire a torpedo, and they would scoot right underneath and go on their way.”

“We made every New Guinea landing from Milne Bay through Morobe, Finchhaven, Dregger Harbor, Hollandia, and Itopi. We helped bombard the landing area if an LST got stuck, we went in and pulled it off.”

“From New Guinea, we went to the Admiralty Islands and started making landing there. We had a Marine unit and the Eighth Calvary unit on transports. The transports laid offshore with a destroyer screen, and the rest of us went in and bombarded the shoreline and hills in the background. We had one 8” Jap battery that gave us a little trouble, so they called in a squadron of Australian spitfires. They took care of that in short order.”

“Around noon things seemed pretty quiet, so the Marines went ashore and started working back toward the hills. Then the 8th Cavalry went in and the Marines came back to the beach ready to go back aboard the transports. Something happened and the Marines went back in again.”

“Another Chief and I were always fishing. We had our own little fishing boat on board. Anyhow, when we were finished with the bombardment and everything ashore was going along quite well, Tupko, the other Chief and I decided to go fishing, so we got permission to go and lowered our boat over the side and took off. We saw a school of tuna or maybe skipjack over between the islands. We got there and caught several when we happened to notice the Marines were setting up a battery of 105s and 50 cal. machine guns on the point of one island. They let go with a salvo of 105s and then the 50s took off. They went right over the top of us, except the 50s. They went ‘chunk, chunk’ all over the place. Needless to say, we got out of there.”

“That night Jap snipers gave us a little problem, so a squadron of P.T. boats came in from somewhere and machine gunned the area all night. The next day saw everything much under control and secured.”

“We left and went back to Hollandia to do some salvage work on a sunken Jap ship. She was in a 110 feet of water and, of course, the water was warm and clear as a crystal. We brought up some small deck guns and a big trunk full of maps and charts. all classified information. Apparently, intelligence knew this material was on board. The ship was scuttled, probably to avoid capture.”

“When we finished with the salvage work, we decided to get a few fish. The area around that ship was full of red snapper. We lowered a 50# box of TNT with an electric detonator, moved the ship away, and set it off. We picked up fish for an hour. Some weren’t worth picking up, but we got enough good ones to give us fresh fish for a couple of weeks!”

“Then back at Sea Adler Bay in the Admiralty Islands to check on things there. We had been gone about a month.”

“One evening, I was sitting down in the Chief’s quarters reading Our Navy magazine. It was the February 1944 issue. I was checking the list of newly appointed commissioned officers, and there was my name as big as life. This was May 1944 and the list was of January 1944. I didn’t waste any time rounding up the ships Yeoman. He checked on all the past bulletins and sure enough, there it was. I went to Captain Byerly, and he said, “Pack your bag and we’ll send you back to the States for new construction. All the officers on board donated a part of the uniform for me to get back to the States in. So the next morning, I left the ship with my gear and orders that only read, ‘Upon arrival, report to the Commandant, 9th Naval District for assignment.’ So I had to find my own Transportation back. There I sat on my packing box to see what next. I really wasn’t in any hurry.”

“A jeep finally came along, and I bummed a ride to a C.B. camp. I got a tent for the night and a jeep to get to a jungle mat air strip the next morning. I was at the strip at 6:00, and the dispatcher said a C-47 would be in in about a half hour. Sure enough, here he came. They off-loaded a bunch of crates and I boarded and away we went for Guadalcanal. Surprising what you can do when you have a little gold on your cap.”

“Eight hours later, we landed at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. On the way, we circled over New Britton Island. The Japs were still on there, and they took a few pot shots at us, but at 8,000 feet they weren’t too good a shot.”

“Later that afternoon, I made it to the officers’ tent city known as the Guadalcanal Hotel De Gink. Quite a place. Flying cockroaches 2 inches long. You could hear their feet patter on take-off!”

“I was stuck here in this tent city for 11 days with no transportation out. I finally decided to do something about it, so I went down to the boat landing, borrowed a boat, and made a tour of the bay to see if some merchant ship would give me a ride back to the States or somewhere where I could get transportation back. I finally went aboard the SS Celestial and asked the skipper for a ride. He said, ‘Sure, come aboard, if you don’t mind sleeping in the sick bay.’ I said I wouldn’t mind a bit. I went back ashore, and packed my gear, and went back aboard. I also took my tent buddy along. Except for blowing one boiler and having to come back for repairs, we had a good trip to ‘Frisco. It was six weeks from the time I left the Coucal in Sea Adler Bay ‘till I got back to the States.”

“I had reservations waiting at a hotel near 8th Naval Headquarters, so I checked in the hotel and the next morning reported in to 9th Naval. It took 3 days and I had my orders for the USS Apollo under construction in Brooklyn, New York. The 3 days’ wait I spent getting my uniform in order. I had been traveling with a rather nondescript assortment of sizes and colors.”

“So, on the Southern Pacific to Omaha and the Chicago Northwestern to Marshalltown and then home. I had 30 days to get to Brooklyn, so, what the heck, I’ll take it easy.”

“Saw my daughter Charlotte for the first time. What a pretty little girl. She absolutely wouldn’t have a thing to do with me. I asked her if she wanted to sit on my lap and she ran over and jumped on her Uncle Raymond’s lap. It didn’t take too long and we were friends. Larry was different, though, and was a little older and understood what was going on, so we made up right away.”

Meta Mae recalled Hollis’s leave, “When Hollis was home, we decided to go to Minnesota to do some fishing. Hollis had his uniform on which he had to wear all the time, and all the way up and back the gas station owners wouldn’t let Dad use his gas ration stamps. They just gave us the gas free since Dad was in the military.”

Hollis went on, “It didn’t take long for the days to slip by. Meta Mae and I headed for Brooklyn and Grandma Angie (Meta Mae’s mother) said she would take care of the kids if we wanted to leave them. She was very good at that and enjoyed doing it.”

“We saw a lot of the New York area. We lived in the Fort Green housing complex. It was a group of eight story, brick apartment buildings, and we were on the 6th floor of one of them.”

“One night a Navy friend and I moved and entire 5 rooms of furniture across the city on the subway. He needed some furniture for some classes that he was going to teach. We waited until after midnight and we were in uniform. The subway train couldn’t move until the doors were shut, so I jammed the door open until we had all the furniture loaded up. I guess we were in uniform, anybody thought we were doing something for the war effort.”

“I was Electrical Repair Officer on the Apollo with 135 men to repair battledamaged submarines. I spent a lot of time getting repair equipment installed in my 3 shops on board.”

“Finally, in late October, we were ready to head out for the war zone. So, Meta Mae back to Steamboat Rock, and we headed for the Panama Canal and on to Guam to our primary duty of repairing submarines.”

Meta remembered her many trips on the train during the war years by saying, “On my many train trips during the war, I wore an officer’s cap device as a lapel pin, and when traveling on the train, was given special privileges just as the service men and women. During these trips, when we would stop at a station, the USO ladies would be there and they would serve sandwiches and coffee. I was always included and treated like one of them. Maybe there would be a big birthday cake for anyone on the train with a birthday.”

Hollis recalled one little incident on the way to Guam. “A Jap submarine surfaced about 1000 yards off our port bow. We had a destroyer escort and ASR with us. I had the gimmery watch, so I had all guns that could come to bear on the target. I requested permission from the skipper to open fire and the word came back, ‘Permission not granted.’ I would have gotten hung higher than a kite, but I almost ignored the order and opened fire anyway. By that time, the sub crew had manned their deck guns and the two escorts converged on the sub. They abandoned the deck guns and submerged. The escorts made hash out of the sub. We figured they were out of torpedoes or they could have made hash out of us.”

“This is now December of 1944, and things are moving along real well. U.S. and Allied forces are real well organized by now. Our repair crews are working day and night. My men are on 3 shifts in 24 hours, one only assistant officer in the 9th Division. He was a rather old Chief Warrant officer and not too well, physically. He and I took 12 hours on and 12 hours off. That way we overlapped from one shift to the next. It worked out pretty well. Our crew was older men and not too experienced in marine mechanics. However, the lack of experience was made for by willingness to learn and we got a lot of work done.”

“Now it’s the Spring of 1945, and the Germans are about to call it quits. Fleet units from the European theater are now moving out our way and the Battle of Okinawa is in full swing. The kamikazes are at the height of their accomplishments and the 29s are plastering Japanese cities into one big mass of rubble. Why the Japs don’t give up by now, I don’t know. They had nothing to work with. The pilots they had were 16 and 18 years old with practically no training. Except for suicide missions, they didn’t have a chance.”

“Now comes the bomb over Hiroshima, and still they wouldn’t quit. It took another one on Nagasaki to finally convince them that they had better surrender. The war is now over, and we are all thinking about going home. Leaving the area was on a point system, 1 1/2 points per month overseas from January 1, 1939. I had 48 months’ total and 72 points. I had the most points of anyone on the ship. About a week later, I was on my way back to the States. I figured I’d had enough, so I put in for a discharge and was transferred to Great Lakes, Illinois via Seattle, Washington. This trip and processing took better than a month and by the time I got home, in October, the celebrating was over and we missed the fun.”

“Now comes the time of reorganizing the whole system. The war plants are closing down, the workers are going home. The servicemen are coming home looking for jobs and right now there aren’t too many.”

Meta Mae Havens recalled some of the good that the American entertainment community did during World War II. Some of the entertainment and those responsible were remembered like this. “There were a lot of new songs coming out about this time. The big bands were in full swing and I mean swing. The popular dance was the jitterbug and let me tell you, you had better be in good physical trim to keep up with this set.”

“Singers Bing Crosby, Perry Como, Judy Garland, Kate Smith, Barbara Hutton, Dinah Shore, Doris Day, and many more too. The big bands of Guy Lombardo, Kay Kaiser, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, Charlie Spiviak, Harry James, Les Brown, Bennie Goodman, Sammy Kay, Wayne King and again many, many more. And the song writers Irving Berlin, George and Ira Gershwin, Rogers and Hammerstein, and a lot more of these too.”

“The songs were “White Christmas,” “I left my Heart at the Stage Door Canteen,” “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition,” “I don’t want to walk without You,” “Bell-Bottom Trousers,” “The White Cliffs of Dover,” “God Bless America,” “O How I Hate To Get Up In The Morning,” “When the Lights Come On Ogain All Over the World,” “My Dreams are Getting Better all the Time,” “You’re in the Army.” So many good songs. And then let’s not forget the comedians, Jack Benny and Rochester, Red Skelton, Bob Hope, George Burns and Gracie Allen, Jimmy Durante, Milton Berle, Fred Allen were all popular.”

There were many others that served country and community as well. It would have been wonderful to know their full stories as well.

© 2020 Steamboat Rock Historical Society | All Rights Reserved

Powered by Hawth Productions, LLC