SRHS

Steamboat Rock Historical Society

TRAILS BECOME ROADS

BUILDING ROADS

Before gravel, Iowa’s country roads were just plain dirt, a quagmire in the spring and after each rain. But it didn’t make a lot of difference. Most vehicles were horse drawn and cars just stayed home until the sun did its work.

But by the twenties, cars and light trucks were demanding year-round service regardless of weather-particularly on highways like U.S. 30.

In the spring when the frost went out, “the bottom would drop right out” of U.S. 30. Long stretches, 40 rods or so, looked like disaster areas. They would be rutted, axle deep, with potholes full of old fence posts, gunny sacks, and other foreign material which desperate motorists had thrown under their helplessly spinning wheels. Nearby farmers could make a tidy little sum pulling cars out of the holes for a dollar a throw.

Harm Folkerts of Steamboat Rock, met his wife because of a muddy road. He became acquainted with a young lady named Adelaide Muller during a BYPU (Baptist Young People’s Union) convention in Steamboat Rock. Young folks from all the North American Baptist Churches in Iowa met once a year. The various churches took turns hosting the event, Visitors that came from all over Iowa, stayed overnight in the homes of church members.

The west end of Main street in Steamboat Rock in the early 1900’s. Notice the smoke and steam from the creamery that was located near the river left of the bridge.

The first night, Adelaide was riding home with her host family when they got stuck in the mud. Harm evidently lived nearby because he helped them get out of the mud hole, and in the process met his future bride.

Some of the worst areas would be “planked.” The Highway Commission would lay planks, not all over the road, but just in the wheel tracks. It took careful driving and woe to you if you slipped off.

Our ability to travel hundreds of miles in a day on quality roads is actually a very new development coming into being totally within the 20th century. Most in the second half. Intestates came along in the 1950’s under Dwight Eisenhower.

Highway engineering developed in America, between 1900 and 1920.

At the end of the 19th century man was poised for the coming of the transportation revolution. Although the railroad had been carrying men and their goods for 50 years, the automobile was about to reshape the landscape. By 1920 the automobile was available to the public on a grand scale changing man’s expectations of transportation forever.

Suddenly the only barrier to quick travel was the lack of adequate roads. The existing roads were not roads at all, but rough, often muddy paths that in some cases were made many years earlier by the bands of Indian hunting parties. They were somewhat wider now accommodating a horse and buggy, but in some cases not wide enough for two to pass.

In 1904 the Iowa State Highway Commission was established at Iowa State College (now Iowa State University) in Ames. The commission’s job was, at first, to convince the public that a state system of improved roads was in their best interest.

There were many challenges to early road construction in Iowa, but solutions did come from creativity, persistence, and science. Both from within the commission and from private individuals.

In 1913 legislation was passed that expanded the commissions duties and provided funds to establish a staff of trained engineers. By 1919 the commission employed 156 people, and had a payroll of more than $100,000.

Before 1919, road construction usually relied on local materials and the natural landscape. Some communities had experimented with concrete and brick roads, but earth and macadam (gravel of crushed limestone or granite) served as the primary road surfaces. Roads were often little more than graded stretches of ground, cleared of weeds and grass.

For the first two decades of the century, road builders built earthen roads or macadam as the public demanded.

In April 1905 the Chicago & North Western Railway sponsored a train that traveled across the state and put on Good Road demonstrations in various towns. The Burlington Railroad did likewise in the fall of the same year.

The main goal of these road shows was to promote a device called the King road drag. Promoter D. Ward King of Missouri traveled on the trains to instruct local citizens on the construction and use of his drag. The drag consisted of two 10 or 12 foot half logs or planks secured parallel to each other by Iron straps and pulled behind a horse.

Remember nearly all the roads were dirt roads of either clay or loam. If the road surface was of clay, it offered an acceptable surface, but presented several problems. If not properly compacted it would become soaked with water, and mud collected on the tires of vehicles. Clay roads also were difficult to grade. Loam roads were porous and granular in nature. They were more easily graded and could be drained with tile.

After a rain, a farmer or road officer could drag local roads, filling in ruts and enabling the surface to shed water better during the next rain. As long as earthen roads were common, the road drag served as a valuable tool for maintenance.

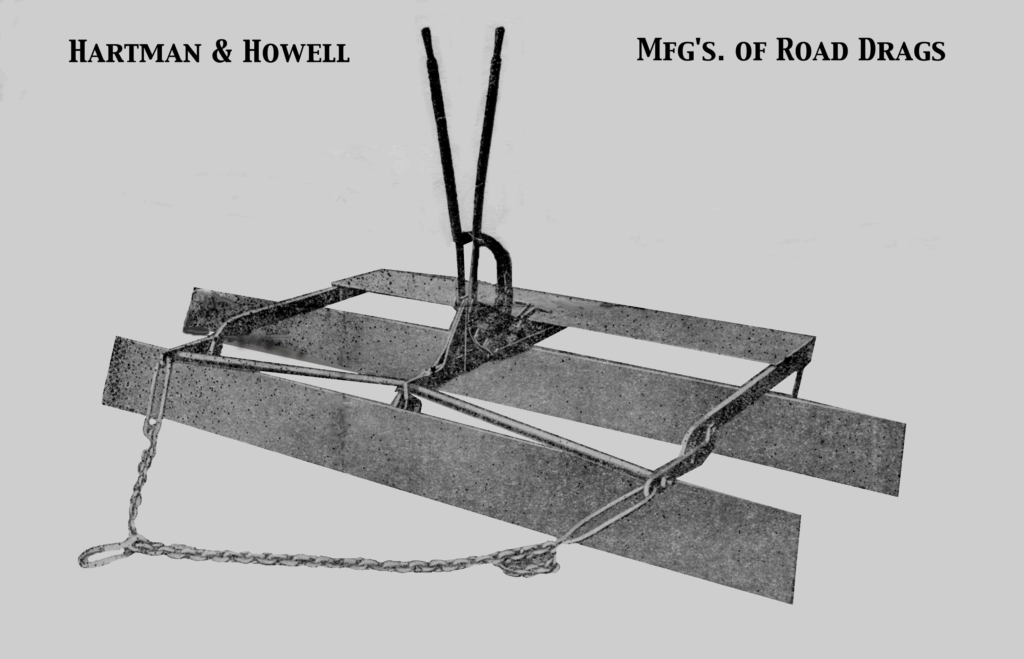

A Steamboat Rock man by the name of Bill Hartman saw that Iowa roads needed a better road drag to eliminate those mud holes and ruts, so he went back to his blacksmith shop and designed one. Unlike the King Drag that had been touted up till now across the state, Hartman came up with an all steel drag. His steel road drag had individually adjustable blades that were controlled by levers from the driver’s position. Bill Hartman became the inventor, manufacturer and salesman of the H & H ROAD DRAG (H & H for Hartman and Howell. Mr. Howell was Mr. Hartmans partner in his blacksmith business at the time but evidently had little to do with the invention of the drag even though his initial graced the products name. Hartman’s invention was the predecessor of the modern road maintainer and was sold to county supervisors all over Iowa and proved to be a great success.

They installed some heavy machinery, to facilitate the manufacture of the drag and later a special truck was built on which the drag could be loaded and hauled behind an auto for exhibition at fairs and the like.

© 2020 Steamboat Rock Historical Society | All Rights Reserved

Powered by Hawth Productions, LLC