SRHS

Steamboat Rock Historical Society

WORLD WAR...AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION

THERE WERE FUN TIMES TOO!

All was not gloom and doom during the depression years. In the early years of the depression Steamboat Rock had a ball team that consisted of Harold Luiken, Harry Luiken, John Eilers, John Cramer, Tony Luiken, Ernie Eckhoff, Carl Sentman, Willard Hartman, Russell Holmes, Frank Smith, Carl Luiken, and Ralph Berryhill.

Steamboat Rock had the first lighted ball field in Hardin County. The lights were built in 1931 with poles cut from Leverton’s timber. Money was raised for the lights, even though this was in the depression.

The team had two pitchers, Harold Luiken and Frank Smith. Harold threw a straight fast ball, and Frank tossed a slow bending ball. When an opposing team began to hit Harold’s fast ball, Frank would come in with his slow curve or vise-versa. In 1933 this combination gave them a winning record of 23 and 2.

In her book, Mildred Dunn Lepper’s recalled how the seasons and holidays were celebrated. They are wonderfully written to give us a feeling of the times she lived in.

”Winters brought fun to young folks in our little town. There were plenty of hills, and if you were lucky enough to have a sled, you could go coasting. If you had no sled, you could try your luck attempting to coast on a shovel or a big tray if your mom would let you use one. If you had none of these, you could perhaps ride along on a friend’s sled. The big boys made bob sleds they called “easterns”, and if you were in the right place at the right time, maybe they would pack you on with four or five others. We sometimes rode from the top of Grieves’ hill on down across the ice on the river. In time, I managed to save enough to buy a little sled of my own, Dan Patch was its name. Now I could go like the wind, “belly buster”. Roots hill was another favorite sledding place, but it has long since grown over with trees and brush. It was right west of George and Lydia Potgeter’s home. My mother said that in her young days, there was a hotel or boarding house run by people named Root, and that was why the hill got its name, just as Grieves’ hill took the name of Harry and “Linnie” Grieves. Their daughter, Lucy, and I were classmates.”

“Another winter sport, especially for little ones, was lying on your back on a snow bank and by waving your arms up and down, you made angels in the snow. Of course there were snowmen, snow forts and snowball fights. It was not until I was a teenager that I learned to ice skate. That was not too hard, for I had learned to roller skate. Our roller skates had been brought along in the trunk with our other belongings.”

“The woods around Steamboat Rock came to life in early spring and any child fortunate enough to grow up there, learned where to find the first wild flowers. Peeping up from under the shelter of moss covered fallen tree trunks and branches were little pink spring beauties, snow white anemones, hepaticas and dog tooth violets In time for May baskets, we could find Dutchman’s breeches, bloodroot, blue bells, bleeding hearts, purple violets and more. It was fun to make May baskets to hang on our friends’ houses, usually on the door knob, and we started making them long before the first of May There were not many little boxes to use in those days as there are now, no pretty plastic containers such as what strawberries now are sold in, cottage cheese containers and the like. We used scraps of wall paper or other pretty paper we had saved. These were cut, folded and pasted into cornucopias, triangles and squares, and filled with flowers and sometimes pop corn for an extra treat. On the evening of May day, we crept up to a friend’s door, hung the basket, knocked and ran and hid as we shouted, “May Basket!” to the top of our lungs. The lucky recipient tried to catch the donor, and a jolly chase ensued, ending in hugs or whacks, depending upon the degree of friendship between the two.”

“The last of May marked the end of our school year, and this, like the beginning, was both joyous and a little sad. The teacher had kept our best work we had done throughout the year, and there was an exhibit the last day. Parents and others interested could come view what had been accomplished. It provided incentives to do the best we could. Pity the careless sluggard who would not, and the slow learner who could not pass the grade. It seemed to me that would be a disgrace I could never survive.”

“Sometimes there was an end-ofschool program. Memorial Day came either on or right after the close of school, and that was a big day, too. I wore my white embroidered dress, if I had not grown too big for it. In that case, I inherited my sister’s old one, and if she was lucky, she had a new one. One thing was certain, I always grew taller, not wider. With a new hair ribbon and sash to match, perhaps sent by the aunts in Chicago, I felt quite elegant. All of the children marched to the cemetery, following the town band and carrying little flags and bouquets of flowers which we placed on each soldier’s grave. There were metal markers stuck into the ground at the head of each grave, indicating which war that hero served in. It was a very important ceremony to take part in. Riding in the parade were several old “boys in blue”, as these veterans of the Civil War were called. My mother’s father, Jerome Seabury, had fought three years in that war, and although I was an infant when he died in 1909, I felt close to him because of the stories our mother told us that he had told his daughters. He had been an excellent singer, and mother often sang those old war songs to us, such as “Tenting on the Old Camp Ground”, “Marching Through Georgia”, Shouting the Battle Cry of Freedom”. He had served in the cavalry and was on Sherman’s march to the sea. Toward the end of his service, he was thrown from his horse and suffered an injury from which he never entirely recovered. He spent some time in the hospital in Nashville, Tennessee.”

“The Civil War veterans were getting to be so feeble, they rode in a car in the parade. I cannot recall having seen a soldier of the Spanish-American War, but there may have been one or two in Steamboat Rock. The khaki-clad young men who returned from the big World War had uniforms that were very different from those worn in previous conflicts. Their trousers were like riding pants and they wore leggings made of strips of matching cloth wrapped around from their shoe tops to their knees. Spats also were worn. The coats came to below the hips and fit in tighter at the waist, and the collar of the coat stood straight up, buttoned with brass buttons from collar to the bottom. Their hats were like Smokey the Bear wears now. Of course Smokey’s hat was copied after the soldier’s hats. The highway patrolmen wear the same kind now. There were also caps that folded flat. They used to call them overseas caps, and veterans of World War II wear that kind today In the first World War, the color khaki, or olive drab, was chosen, we were told, instead of blue because it was more of an earth color a blend of green and brown. The men in the Navy wore navy blue or white as they do today. To this day I feel a thrill when the parade goes by on Memorial Day, and memories of parades long ago flash through my mind. How many, many bouquets my dear Aunt Essie furnished for those parades in Steamboat Rock.”

“Another special day was Easter. Bunnies, chicks and eggs loomed high in my earliest recollections. Easter of course came before Memorial Day, and that was the first spring day to don the white embroidered dress, all freshly starched and ironed after a long winters rest in some trunk. In our Easter bonnets, if not newly made ones, then the old ones perked up with new flowers and ribbons, and hopefully wearing a new pair of Mary Jane slippers, my sister and I proudly stepped out to church on Easter morning. Learning the deep meaning of Easter was to be a gradual process.”

“The deep meanings in life take a lifetime to absorb, so it is fitting that our childhood memories be happy and light.”

“Of course it was our mother who filled and hid our Easter nests, even though I was sure it was Mr. Rabbit. One wonderful Sunday in Excelsior Springs my birthday came on Easter. I think it may have been my eighth. Beside my nest was a box of twelve marshmallow bunnies! Oh what bliss! I can see that box now, nestled in the grass out by the wood shed. I cannot remember, but I hope I shared them with my brother and sister!”

“Children’s Day was another special day at church. It comes in late spring and we always had a program in Sunday School with recitations and songs. The Children’s Day I remember most vividly was when I was about twelve years old and we were attending the Congregational Church in Steamboat Rock. It was in the same building that is now the Presbyterian Church, but has been changed and enlarged. Another girl and I were to take up the offering. As I had never had this privilege, I was quite excited about it. Dorothy put my hair up on rags the night before. Putting one’s hair up on rags is a custom long past, long before electric curling irons or permanent waves were invented. The locks of hair were dampened and separated into strands all around the head. Each strand was rolled up on a rag strip and tied securely in a knot, until all were tied. This was not too painful to sleep on, in anticipation of having beautiful curls the next day In the morning she unrolled them all and brushed each strand around her finger. I would not believe that was my image in the mirror! How proud I was to pass the offering box on its long handle! Oh, woe was me! When I was walking down the center aisle, right over the hot air register in the floor, I bumped the box in such a way, that the coins rolled out in every direction, but most of them went through the little squares in the register! I was old enough to have heard that wise saying about “pride going before a fall,” but oh, how I hated being reminded of it. Why must life’s lessons be so hard?”

“Until I was about thirteen, I had little use for shoes in the summertime. The same was true of my chums. What joy was ours, walking through the dewy grass at morning play; feeling the cool mud oozing between our toes after a morning shower! Of course this pleasure was not without its dangers. I remember well when I was swinging, and dragged my foot, top side down, over the ground. A sharp pain and rush of blood sent me crying for mother. There was a large gash which left a nasty scar I shall keep always’ Mother did not take us to the doctor unless it was extremely necessary in those days. She dressed the wound as best she could. This happened in Excelsior Springs before I started to school. Mama’s courage saw us through all the childhood diseases – mumps, measles, whooping cough, chicken pox, colds and even the Spanish influenza. We had them all. The only thing we were vaccinated for was small pox. Since I was the youngest, I had childhood diseases the “lightest”, or so my mother said. I can not remember any of them except some colds. We were a fairly healthy lot, fortunately.”

“By the time we lived in Steamboat Rock, I was old enough to be trusted to go wading in the “safe” places in the Iowa river. Since my mother had spent her early childhood in that town, she, too, had waded in that river, and knew the shallow places. Our favorite spot was in the “riffles” down at Tower Rock. The first time I viewed this special place, I was accompanied by my newly found friend, Alice Potgeter. She knew the safe as well as the deep and dangerous places, for she had lived in a big house near the river all her life.”

“To get to Tower Rock from where she lived on the west side of the river, we crossed the bridge and followed the road east, up Grieves’ hill, then a little farther on to Root hill, which led south, over the Elk Creek bridge. There we turned west and followed a path that took us to the top of the big Steamboat shaped rock along the east side of the river. We could make our way through the brambles consisting of scrub oak, bitter sweet and wild grape vines, until we climbed down over a stony abutment leading to a large open space below. What a fairyland! Even though I had seen beautiful Crater Lake in all its glory, this sight still awed me! To our left was a high rocky cliff, which Alice told me was Tower Rock. Little trees of many kinds sprang up from the crevices in the rocks. Seeds falling from tall pines, oaks and birches above had found nourishment enough to take root in the forbidding rocks below. Ferns and wild flowers, too, had found a footing and added their beauty to the mossy bank. At the foot of Tower Rock, and as far up as anyone could reach, countless sets of initials had been carved in the bare, vertical base. There was history there, for the dates went back to the late 1800’s. Occasionally a carved heart joined the initials of two lovers.”

“A cold spring bubbled up at the foot of the cliff and we kneeled down for a drink of the delicious, icy water. Long legged water spiders darted over the top of the water and kept us at the spring watching for a while. We sent little leaf boats sailing down the tiny, dear brook that flowed from the spring on down to the river. This whole area from the rock to the river edge consisted of fine damp sand that felt delightful to our bare feet, and was fun to make tracks in. We made castles that day and many at other times.”

“The place known as the “riffles” was where the river spread out wide and shallow, and in those days, the water was clear enough to see the rocks over which the water was rapidly flowing, after making its way slowly through the narrow, deep place farther upstream, below the big steamboat shaped stone formation that gave the town it’s name. It was dark there and quiet, and Alice told me it was very dangerous, so we could not wade there.”

“At the shallow places, we could watch minnows that congregated in still small pools at the water’s edge. There were many clam shells shining among the stones in the river bottom. Alice picked up a live clam with its shell partly open, and when she stuck a little stick inside, Mr. Clam quickly clamped down on the stick, breaking it. I learned that the clam would be worse than a mouse trap had it been a finger instead of a stick!”

“Tower Rock was going to be one of my favorite places, I was sure. The William Sharpshair family farm was at the top and on east of Tower Rock, and one could walk right past their place, coming or going. Later I came to be good friends with the older Sharpshair girls, Marie, Louise and Dorothy My mother told me that when she was a young girl in Steamboat Rock, her parents, Jerome and Mary Seabury and the elder Sharpshairs, William, Sr. and Honora, were acquainted, having come to the area not long after the end of the Civil War. My grandmother, Mary (Taylor) Seabury and Honora Sharpshair were near the same age, and became good friends. Grandma was born in Illinois in 1850; Honora in Ireland in 1848. Honora could remember about the terrible potato famine in her homeland. Her family came to America in 1865. The Sharpshairs had several daughters and a son, and the Seaburys, with their young daughters rode with the Sharpshairs in their team and wagon to the Hardin County fair in Eldora. That was something very special as mother remembered the trips so clearly, and spoke of those times often. These children all attended the school at Steamboat Rock, which was built in 1869 – the same building where I went to school upon arriving in 1918, only the children I went to school with were the grandchildren of the older Sharpshairs, William, Sr. and Honora, just as I was the grandchild of Jerome and Mary Seabury”

“I used to think it would be fun to live by the river as the Potgeters and Sharpshairs did. I think I felt a twinge of envy living in the old restaurant where we had no yard at all. The Sharpshairs owned Tower Rock, and the Potgeters owned the elevator!”

Tower Rock

“One occasion looked forward to each year was the Sunday School picnic held at Fingers’ pasture south of town. There were lots of good things to eat, and contests such as three-legged races, sack races and just plain foot races.”

“Taking our cue from this jolly get together, a few of us girls would sometimes gather up what edibles we could find in the cupboard and have our own picnic adventure. A favorite place was up a ravine in Fingers’ pasture. We called this spot sleepy hollow. We would build a little fire and roast wieners and marshmallows, if one of us was lucky enough to obtain these at home. Sometimes our picnic was so slim, it could not be called a picnic at all, but it was a jolly adventure just the same, with giggles, riddles and tall tales. In spring, of course, there were flowers to pick and take home with us, and in fall, nuts to gather – black walnuts, butternuts and hickory nuts.”

“If there were organizations to belong to, such as 4-H, Girl Scouts and the like, I did not hear about them. Many had to furnish their own entertainment but did not know what boredom was. There was no roller skating rink, but we skated on the sidewalks all over town. Another simple pastime, especially on a Sunday afternoon, was walking with a favorite chum, while first one and then the other shut her eyes tightly and promised not to peek. The “seeing” member of the twosome led the other, hither and yon, for a long way, sometimes letting her feel a tree trunk or other unknown objects. When at last, the led one opened her eyes, she found herself in a strange place perhaps the cemetery, or under the bridge or seated on a bench on Tower Rock Main Street in front of a store. The leader must be careful in leading the “blind” one, or she might steer her straight into a post, as I once did to my dear friend Ruth Schwitters. Giving her a bruised nose. She did not reciprocate, but perhaps she should have.”

“To you, my dear grandchildren, this may seem strange amusement, but I would argue that any blind man’s game helps to develop awareness and alertness, as contrasted to the present occupation of passively sitting before a television set, although this, too, can have its merits, depending upon what one is watching.”

“A day of great importance in my young life was July 4, Independence Day Even as a very small child in Excelsior Springs, I was aware that there was something very special about it. I suppose I could not understand what was meant by “birthday of our country”, but many people hung out the flag and there was a big parade that was different from a circus parade. I loved the sparklers and little firecrackers, but not the big loud ones. In Steamboat Rock I was older, and we celebrated with a family picnic on Aunt Essie’s and Uncle Harry’s pretty yard. The other uncles and aunts came by train. These were relatives of my mother’s side of the family. Aunt Belle, Uncle Clarence and Grace Mary came from Minneapolis; Aunt Bertha, Uncle Cady Barnes and daughter Ethelyn from Manilla, Iowa; and Aunt Nellie, Uncle Ethmer Reece and their three children, Donald, Marcia and Cady from their farm home near Eldora. They would go to Union, Iowa to bring Grandma Seabury Her birthday was on July 9, so we celebrated that, too.”

“Grandma was a real patriot. She had a flag pole in her yard and never failed to fly her flag on all the “appropriate” days. People did not fly the flag just anytime as now, and no one would have thought of leaving it out in the rain, or at night, although rules have been changed now so it is all right to let it fly after dark as long as it is illuminated. Grandma’s favorite tale was about the time when she was a small girl in Freeport, Illinois, and Abraham Lincoln came to town to make a political speech. He was running for the Illinois legislature. Grandma’s father, my great-grandpa, Giles Taylor, had taken his little daughter with him to hear the speech, after which Giles went forward to shake the speaker’s hand. Mr. Lincoln turned to little Mary and said, “And who is this little girl?” He patted her on her head as he asked. She never forgot that, and there was always a picture of President Lincoln hanging on her parlor wall.”

At the crack of dawn one fourth of July, my brother Francis was up early, and he woke up the neighborhood with a tremendous blast. He had the biggest firecracker he could find, under a large tin can, letting the fuse stick out under the edge. When he lit it, everyone knew that the big day had arrived. Children all over town had been saving their pennies and nickels to spend for various fireworks, torpedoes, devils, and sparklers. they were popping and banging until the supply was exhausted. My favorites were torpedoes that you threw hard against rock. As soon as darkness came, we lit the pretty sparklers people in town bought Roman Candles and shot them into the night sky. These were a real treat to watch, but I did not see a public fireworks display until my adult years. These were legal in those days, and Mama even sold some of the smaller ones in the restaurant.”

“Summer time had its advantages and disadvantages. By the time it ended, we were looking forward to fall, the favorite season of many, including myself. It may have been around the fall of 1921 that we moved out of the restaurant and into a house. We called it the Beamsley house, and it was roomy, with an upstairs and there were green shutters at the windows. My mother had married Bert Carpenter, a friend of her early years, who had once worked in the flouring mill at Union, Iowa, and later at the wood buggy works, painting the buggies. He had never married, and had now come to live near his aged mother in Steamboat Rock. He worked with Harry Grieves and his road crew who built many bridges in Hardin County. Bert cooked for the men and was proud of his cooking. He was a kind man and we thought a great deal of him, and enjoyed his sense of humor.”

“I was getting to be a big girl, and once in a while I earned fifty cents for baby sitting with little neighbor kids. Bert hired me for ten cents a night to stay with his mother because she did not like to stay alone. I liked little grandma Carpenter and did not mind my task, although I did fear she might get sick and die some night and I would be all alone with her. She had no telephone and neither did we. I slept on a day bed in the living room and every night before bedtime, I had to rub her back which was all wrinkled and bent and reminded me of a shriveled potato. She was kind to me and wanted me to stay for breakfast before leaving for school, but I did not stay very often.”

“My sister had gone out to Oberlin, Kansas, to live in the home of another of our father’s brothers, Uncle Phil Dunn and family, and attend high school there for her last two years. Decatur County High School was a much larger school than the one in Steamboat Rock, where she had attended her sophomore year. The Kansas school also had a normal training course. Uncle Phil and Aunt Alice had five children. One girl, Clara, was the same age as Dorothy, and Uncle Phil had invited Dorothy to come out and live with them. They graduated in 1921 with Teacher’s Certificates to teach in Kansas. Since there was a shortage of teachers in Iowa at that time, she taught part of a year on a temporary certificate in Steamboat Rock then attended Iowa State Teachers’ College at Cedar Falls, and acquired her Iowa certificate, teaching in a rural school near Wellsburg followed by two years in Albion and several years in Miles, Iowa. She attended college in the summertime at Iowa State Teachers’ College.”

“My high school years were spent in Steamboat Rock, graduating with the class of 1925, a month past my seventeenth birthday. As a freshman, I took Algebra, English, General Science and Latin. The only domestic science – (now known as home economics,) I experienced, was in the eighth grade. There we girls studied sewing and cooking on alternate Fridays, so I did not learn a great deal. When, as a freshman, we had a choice of that subject or Latin, I chose Latin and have always been glad I did. It helps so much in spelling, and by learning the root source of many of our English words, as well as their meaning. We had a very good teacher, Fred Kutzli, who was also the school superintendent. I liked English, also, and Lida Leslie was thorough. We had a good understanding of grammar with practical application in theme and letter writing. We had an introduction to good literature right there in that tiny little school of ours. One excellent English teacher that I shall always remember was Miss Fannie Potgeter. She later went on to earn a PHD and taught at Iowa State University.”

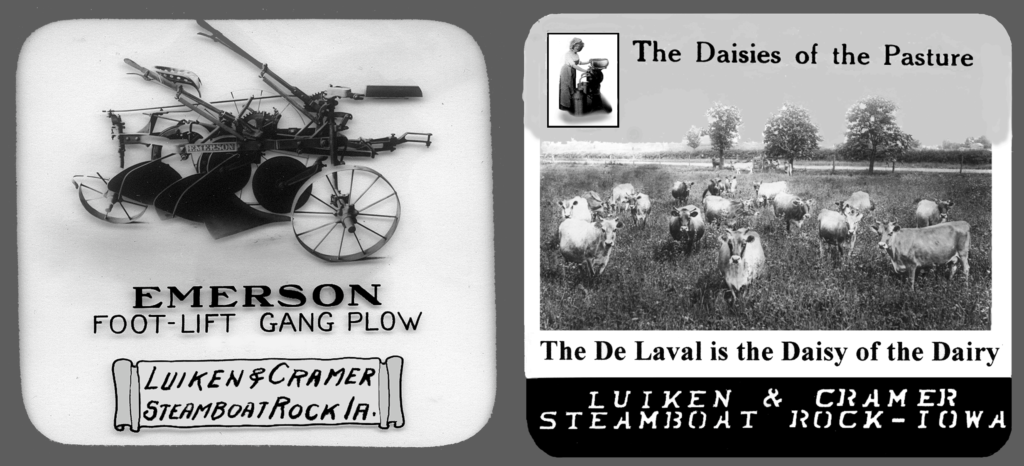

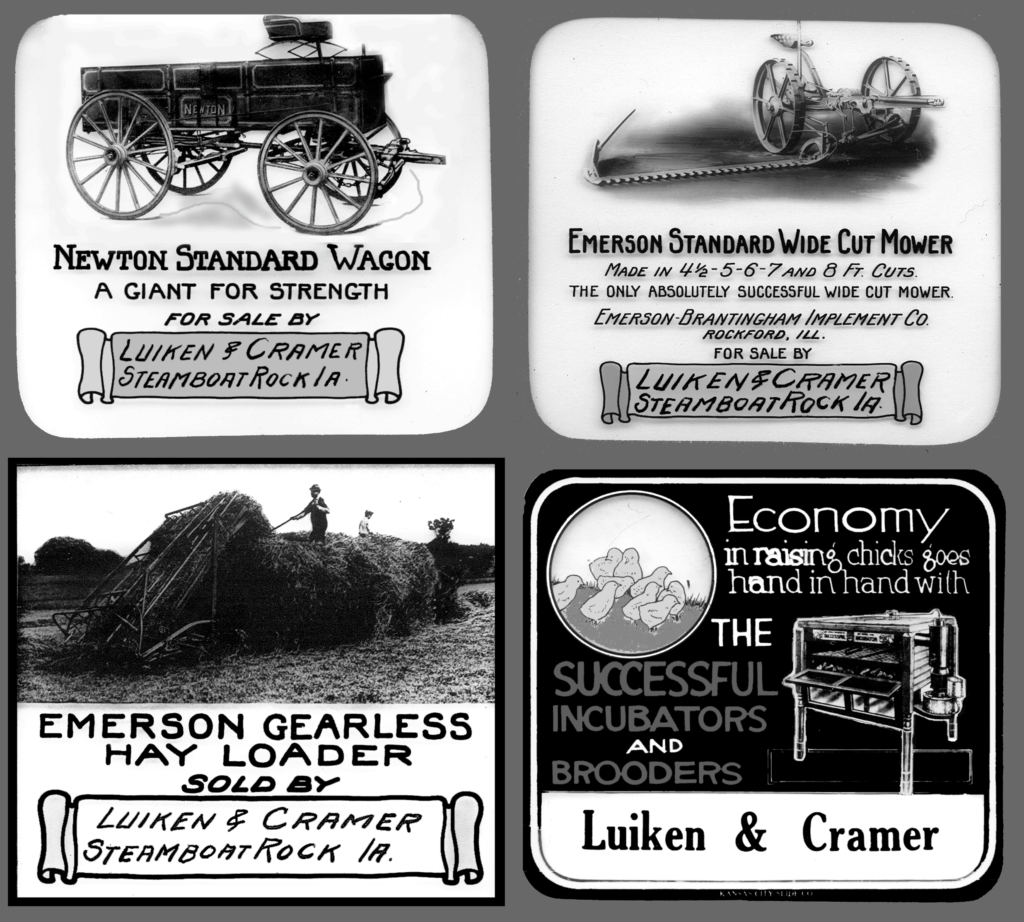

The building on the far right is the building that was once the Unique Theatre. Just a portion of it can be seen and there are no other known photos available. The building later served as the school gym and was used for plays and graduations. Below and right are six intermission slides as they were called used at the Unique Theater advertising Luiken and Cramer implement in Steamboat Rock. Intermission slides were used between reels and when the film broke. Some were used to make theater announcements and said things like, “Ladies please remove your hats,” or “Don’t spit on the floor.” Those shown here are about 4 inches square, made of glass, partly hand painted and in full color. There are 8 of these slides still in the possession of Harry C. Luiken, who’s father Louis Luiken was owner with Jake Cramer of the implement dealership the advertise.

“I never was much of an athlete but was persuaded to learn basketball, as it took all the players that could be mustered. This had not been tried in Steamboat that I know of, and the old 1869 school building had no such place as a gym. At one time there had been a small movie theater at the west end of Main Street. It was aptly named the “Unique”, and a sign hanging out in front of it, proclaimed that name. The movies were not well patronized and many of the citizens thought watching movies was some sort of sin. At any rate, the school-fathers saw fit to buy the building for use as a gymnasium and auditorium, of sorts. The ceiling was so low and the building so short and narrow, that it took some special maneuvering on the part of players and spectators alike to send the ball where it needed to go, and also to dodge the approaching ball. There was only a small space at one end for bleachers, and at the opposite end for a little stage, so spectators crowded in as best they could, spilling out onto the playing floor, for the attendance was very good.”

“In those days girls wore large black bloomers, pleated to a band around the waist and gathered into elastic at the knees. Most people made their own, and if you could afford to buy ample material, you could have more pleats and fullness – the fuller the better. A white middy blouse was worn with a sailor collar and long black tie. Long black cotton stockings and any sort of tennis shoes completed the outfit. Teams from all around dressed the same. It was not until somewhere in the thirties that uniforms began to change, first to short skirts with pants underneath and blouse to match, all in the school colors. These were rather shocking at first, considered by many to be immodest, but certainly more comfortable than the heavy, hot pleated bloomers, and much prettier.”

“The old Unique was not equipped with showers. At that time there was no public water and sewer system in Steamboat Rock or many little towns, although a few of the affluent citizens had their own water supply and septic tank.”

“A few school entertainments were put on at the old gym, even though the quarters were cramped. One rather elaborate operetta by the elementary grades had some little dance numbers, but there was a prompt stop to that. The very word “dance” brought raised eyebrows in Steamboat Rock, even though right after World War I there had been some public dances held for a while in the old abandoned furniture building on Main Street, to welcome the soldiers back home.”

“I enjoyed being in plays, glee club and declamatory contests. By taking part in basketball and declam, it meant getting to go to other schools now and then. Not many people had cars, and there were no buses as yet except the horse drawn ones which brought the rural kids in to school. I was glad I didn’t have to ride to school in one of those, for the pupils got very cold on wintry days. Some heated bricks and soap stones to help keep their feet warm on the long, slow ride. Others stayed in town with relatives during the winter. Still others did not get to go to high school at all, even though they may have wanted very much to go. Remember, my dear grandchildren, the roads were very poor then. They had not been graded up, but were flat with the land, with no ditches for the water to drain into. Graded and graveled roads as you are used to, were not to come until much later. Dirt roads were all right in dry weather only When snow was deep, farmers often opened the fences so they could drive through the fields with a team and bob sled to get to town for necessities. School was not counted as a necessity by some farm folks, but for children living in town, even the poor ones could have the advantage of going to high school.”

“Looking back upon those four high school years, I now know how fortunate I was. Naturally I did not realize this then, and must confess to feeling shabbily dressed sometimes, wearing hand-medowns and made-overs, while it seemed some always had stylish clothes. How trivial this all seems now. It is good this did not bother me too much at the time, either. Certainly I knew better than to worry my mother about my selfish thoughts. I had learned better from little on.”

“While we were in the restaurant, Mama bought a loom so she could weave rugs to sell, as well as making them for others who brought their own rags ready for weaving. She used to tell about an uncle of hers, Asel Wickham, who was the second husband of her father’s sister, Aunt Ermina Seabury. Their home was near the foot of Grieve’s hill and as a small girl, my mother used to watch Uncle Asel weave yards and yards of rag carpet. In those long ago times of rather crudely built homes with rough board floors, it must have been a luxury to have any kind of covering for a floor. Every scrap of worn out clothes and bedding was torn into strips by the thrifty house wife. The strips were sewn end to end, rolled into balls, and taken to the weaver to be made into long rag carpet strips. These were usually eighteen to twenty-seven inches wide and the length of the room to be carpeted. When the weaver had them ready, the owner sewed them together, side by side by hand until the whole floor could be covered, wall to wall. Before putting the carpet down, clean bright straw was spread all over the floor. It took several members of the family to help lift the finished carpet into place and then tack it down firmly, stretching so it would lie straight. The new carpet puffed up over its mat of fresh straw, making the floor warmer and quite soft to walk upon. Only the “best parlor” could boast carpeting. All this was before my time, but I listened to the oldsters tell about those days, and I can remember my grandma Seabury had rag carpeting on her stair steps going upstairs.”

“Owning a loom had been one of my mothers’ heart’s desires, and she put many an hour into weaving away until her shoulders ached, pounding the woof (the rag strips) to make them tight, and then locking the warp by pressing the treadle with her foot. When she had used up all the warp, new spools of warp must be put in place and then threaded through the reeds and nettles, and it was my job to put the warp through all those spaces, while she sat on the opposite side of the loom and hooked each thread through to the front. She had helped her Uncle Asel Wickham thread his loom in Steamboat Rock as a child, and listened to him tell of his experiences as a soldier in the Mexican war and Civil war also. The 1883 Hardin County History tells that he was sitting at his loom when he died in 1880.”

“I must say I did not like threading the loom and dreaded each session, glad when it came to an end. When it was all threaded, she was ready to make a new creation, and she would plan to arrange the rags just so, to form a pretty rainbow of colors. She wound the rags from ball to shuttle, and threw the shuttle from one side to the other in the space between the separated warp. Then when she stepped on the treadle, the warp would lock around the rag strip, and she would beat it tight with the big cross bar, ready to repeat the whole process from the opposite side. Whenever we entered the house and heard the resounding bang, bang, we knew Mama was at her loom. I learned to weave, too, and to help tie the fringe at the ends of the small rugs, but it was not my favorite thing. Surely my dear mother must have stayed at the task until she was very tired, many a time. When rags were brought for weaving that lacked color, she would often dye some of them to make a bright stripe where needed. She boiled these in a wash boiler, stirring with a stick. There was no “instant dye” then. Walnut hulls made a deep brown; beets a beautiful red. People brought old garments sometimes for her to use in rugs, or to make over to wear, and she was clever at the latter task, too, for she was a good seamstress.”

“She taught me how to lay out a pattern and to cut and sew my own clothes, which I did from the time I was in high school. At that time paper patterns were not printed with instructions as they are now, so the task was more complicated and took longer, but I very much liked everything about garment construction, ever since I used to sew for Toots, the doll described earlier in this story. However, that sewing was by hand, now it was on Mama’s old treadle machine. More of my creations came from the rag bag than from new material.”

“All things considered, I enjoyed my high school years very much. As a sophomore, I had another year of Latin under Prof. Kutzli, also English, ancient history and geometry My English teacher in the junior and senior years was my ideal. She was Fannie Potgeter, Alice’s sister, and I wanted very much to be like her. She encouraged her students to do their best. I did not realize at the time that I was missing a lot by not getting to learn typing, but this was not offered in many small schools at that time. I believe some things I did learn may have been as valuable or more so.”

“In the spring of 1924, my junior class, a group of eleven, entertained the seniors at the junior-senior banquet, held at the old Unique theater building which was still used as a gymnasium. We did not call it a “prom” because we were not allowed to dance. Dancing was considered a sin in many small towns at that time. We did not know how to dance anyhow, so did not feel cheated. The old Unique was our “banquet hall”, all decked out in crepe paper and flowers. All the girls were resplendent in their new “banquet dresses”, which had been planned and talked about for months in advance. My sister, who by this time was teaching school in Albion, bought the material for mine, and Mama sewed it. It was Copenhagen blue silk taffeta, made with a Basque waist and full gathered skirt, with flowers at the waist line. I thought it was elegant. The mothers cooked the meal and the sophomores served it. There was a program afterward. The whole affair did not last so very long, after which everyone went home.”

“The senior year’s banquet the same, and also was held at the dear old Unique. We sent for my dress from a mail order catalog. It was periwinkle blue, a lavenderblue crepe back satin. It was not silk as the junior one had been, but a new “artificial silk” called rayon. The next summer I was wearing it in the rain. The dress shrank so much that I could never wear it again.”

“The graduation exercises for the Class of ’25 were held in the Congregational church. Caps, gowns and mortar boards had not been worn by graduating high school students in Steamboat Rock. The girls wore light summer dresses. Mine was pale green voile trimmed with black lace. This, too, was made by my mother.”

“Dorothy lent me one hundred fifty dollars of her hard-earned teaching money, and I agreed to pay it back as soon as I could earn some myself. With this amount I attended college that summer at what was then Iowa State Teachers’ College in Cedar Falls. Several others from my class attended that summer also. I roomed in a private home, and soon made the acquaintance of other girls staying there and enjoyed the whole experience very much. There was a little electric interurban train between Cedar Falls and Waterloo. Several times some of us went there to see the “big city”. I did not go home until the summer was over.”

“I passed the teachers’ exam with no trouble, and prized my teachers certificate even though I would not be old enough to teach for another year; having just passed my seventeenth birthday when I graduated from high school, and one must reach the ripe old age of eighteen in order to teach.

When the train took me back to Steamboat Rock after that memorable summer in college, I found the family all packed and ready to make the move to Marshalltown, hopefully to better ourselves. Mom and Bert had friends living there, a retired couple they had known in their young days in Union. Bert and Charlie Carters had painted buggies for the buggy and carriage works there. Charlie was acquainted in Marshalltown and helped Bert get started in the painting business there. Bert’s mother had passed away a year or two before, so there were no ties holding us in Steamboat. We moved into a large house on West Church Street and Mama kept roomers and boarders. I walked the streets of the town until I got a job clerking in the Art and Baby Shop, located on West Main Street where Apgar’s Studio is now.”

© 2020 Steamboat Rock Historical Society | All Rights Reserved

Powered by Hawth Productions, LLC