SRHS

Steamboat Rock Historical Society

MOVING BEYOND THE OLD LIMITS

TRAIN WRECKS

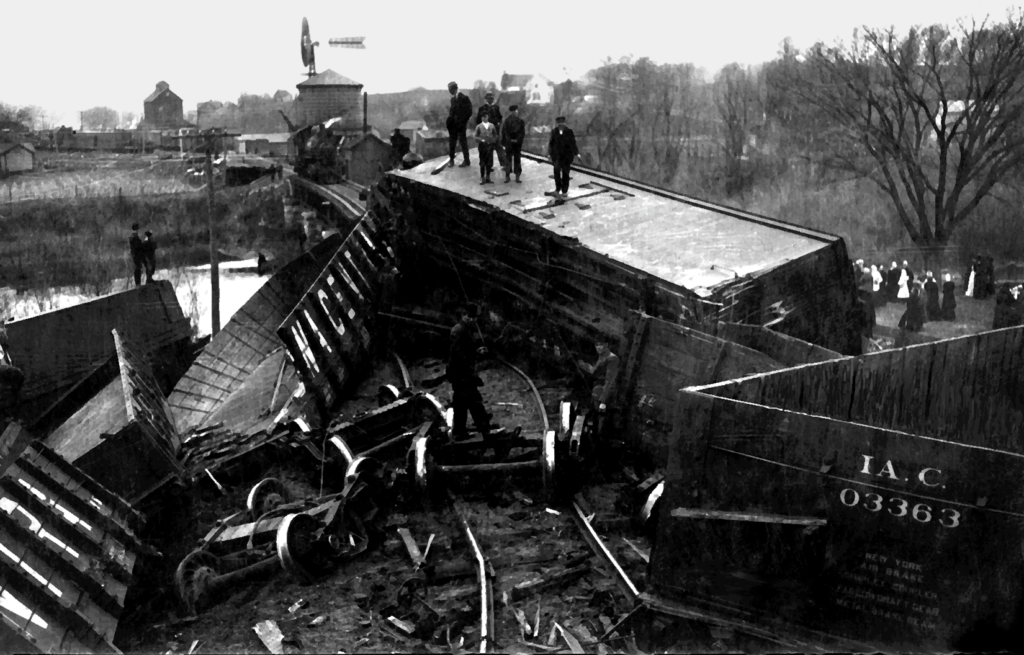

A serious train derailment caused a freight to plunge through the railroad bridge spanning the Iowa River at Steamboat Rock on the afternoon of April 26, 1911.

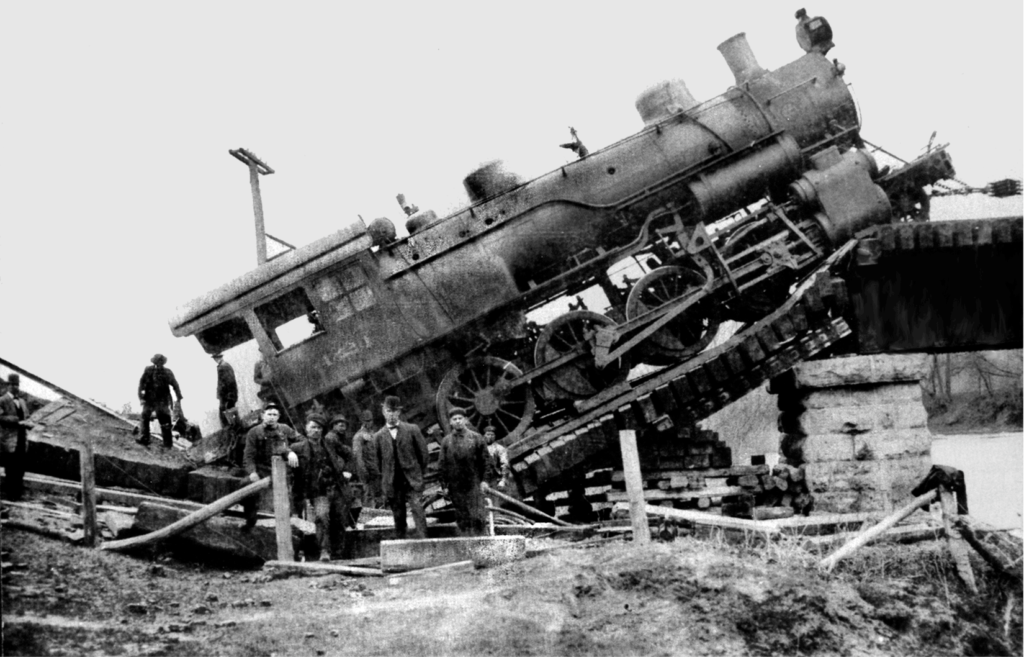

According to the trainmen the derailment of a refrigerator car, the first car after the locomotives, was the cause of the wreck. It left the track about 200 feet north of the bridge. The engine tank ahead of it was dragged off and the cars following it were also derailed before the bridge was reached. The derailed tank and cars struck the north end of the steel bridge over the river and tore out the two north spans causing them to fall into the river. Others were piled up along the track and right-ofway approaching the bridge. The head locomotive got part way across before the bridge was torn loose, then it partly toppled off the bridge.

When everything came to rest a large iron girder of the bridge was run through the locomotive tank, and an immense wooden beam was forced through the firebox of the locomotive No. 421.

Twelve empty and six loaded cars were derailed some being demolished and their contents badly damaged. Among the merchandise in the debris was a car of butter and eggs, one of canned goods, one of lumber, and one of oats. The cars that were empty were reduced to little more than kindling wood. One engine kept the track, and the other was left hanging off the bridge. The track was torn up for some 200 feet. From the standpoint of property loss this was the worst train wreck the company had had in years. It was fortunate that no one was injured.

The engine men escaped injury by jumping from the locomotives as soon as they saw part of the train was derailed, and that the train might go off the bridge. There was no water under the north two spans of the bridge, the drop from the bridge to the river bed was about eight to ten feet. The engineer was Oscar Green, and the fireman was G. Baxter, on the head locomotive No. 100, and J. H. Benson engineer and his fireman J. C. Carberry were on No. 421, second locomotive. Charles Worley was the conductor in charge of the train. It was estimated that the train was running from twenty-five to thirty miles an hour when the derailment occurred.

Through the night that followed no effort was made to get trains through. Trains with the heaviest equipment were detoured at Gifford over the Northwestern, to Webster City, and from there over Illinois Central tracks to Ackley. Lighter trains were detoured at Eldora, over Northwestern lines, to Iowa Falls and from there over the Illinois Central to Ackley. Trains from the north followed a reverse detour.

An interesting side story developed from cleanup of the accident and was later told by the train’s brakeman Robert Burnet.

“The helper engine whistled out a flag. I brushed the worst of the caked mud off my clothes, took a red flag and some torpedoes, and started for the depot. It was deserted, so I hiked on about two miles further until I met a section man from the next town who was out with his hand-car inspecting the track. I told him of the accident. Then we both jumped on his car and pumped up the hill to Eldora. There I gave the news to the operator. He relayed it to the dispatcher, who relieved me from flagging. Thereupon the gandy dancer and I scooted back to the scene of the wreck.”

“Just before nightfall two wrecking trains arrived from each terminus of the Iowa Central. They worked twelve hours at clearing up the mess, after which our train crew was called to handle the wrecker on the south end of the bridge for another twelve hours. All in all, we labored in twelve hour shifts for six days before the freight cars were ready to roll.”

“We all ate our meals in the diner of the wrecker. It was good, healthful food. About the first thing the cook did was to make a raid on the butter-and-egg car. Broken tubs of butter and cases of the best Iowa eggs were hauled to the diner. For six days we sat down to repasts of eggs fried in butter, boiled eggs, stirred, scrambled, and poached hen fruit, washed down with eggnogs. All the vegetables and meat that came off the stove were swimming in butter. This we agreed was real eating.”

“But after three days of this delectable fare I sat down to another egg and butter meal and it suddenly dawned on me that the eggs were just about as delicious as castor oil flavored with garlic. I couldn’t look another piece of hen fruit in the face; and butter didn’t taste so good as it used to, either.”

“Whenever we had time to ourselves after work or during meals, our crew would chat about the accident…

“They told me that the shake stated when the tank of the small girl left the rails, throwing the big engine off. The first nineteen cars followed suit. Inside of a couple minutes the whole front of the train was occupying the space usually allotted to four cars.”

“When we finally crawled out of the cab,’ Joe Carberry said, ‘we looked back at that awful mess and we felt sure you were dead. Why, that gone you had been riding in all day was right on the bottom of the whole shebang! Boy, were we glad to find you!’”

In Abbott, the last stop before Steamboat, Burnet had coupled on the helper engine and examined the head end of the train. Getting a register check and some orders from the conductor. He delivered the information and gave the engineers the highball. What he did next spared his life. His story continued, “I gave the engineers a highball, and right at that point my guardian angel signed the board and went to work for me.”

“I squatted down on my heels in readiness to catch my gon (gondola car), but for some reason I watched the train go past, forgetting completely to board the car I had traveled on all morning. When the crummy came along, I mounted it and swung my flag in a highball and was not answered from either engine. Skipper Worley and Fred Hammell, the hind brake, were so surprised to see me that you could have knocked them over with a giant crane. I had always ridden the smoky end, winter and summer, rain or shine. This was the first time I had ever interrupted a game of cards in the caboose, but here I was in the rear of the train where I had no business to be.”

“I left the caboose via a cupola window and headed over the cars. Our train was proceeding slowly down the Iowa Valley toward the river. I scrambled over the tops as fast as I could, hoping to reach the head before we went through Steamboat Rock…

“By the time the helper engine whistled for Steamboat Rock, I was still about twenty-two car-lengths from the head end. As we were on a reverse curve, I could see both extremities of the train from my position. By now the wheels were turning so rapidly that I had to brace myself even more firmly to keep a balance…

“If the train had possessed wings it would have taken off like an airplane right then and there, but within a half mile her velocity was still greater. I was on the nineteenth car behind the engine, just about in the middle of the train. It seemed to me that the engineers were not speeding like this just to show up a minor defect in an engine. Something must be wrong!”

“All of a sudden I felt the air go on in the big hole. My first thought was that the board was out at the depot, but then I raised my eyes and looked ahead. What I saw convinced me that the train had almost literally taken wings.”

“The butter-and-egg car was tossed up in the air, while the other cars were leaping around crazily in all directions, vertical and horizontal. I could not see the engines because a cloud of dust and smoke filled the air. When the butter-and-egg car had flown high enough, it came down sideways right on top of a telegraph pole, while two venturesome reefer doors sailed over into the cornfield.”

“Things were happening faster than I could make them out, but I gathered that the destruction was heading my direction with the speed of a cyclone. In a few seconds the cars within six or eight lengths of me were buckling up and falling over on the sides. I had to join the birds pretty quick if I didn’t want my young wife cashin in on Brotherhood insurance. Accordingly, I grasped the top grab-iron with one hand and put a foot on the side ladder. I was about to climb down when I realized that the occasion called for speedier descent. So I let go of the ladder and gave one leap out toward the cornfield. Of course, I didn’t reach it. I sailed through the air, not exactly with the greatest of ease, and landed smack in rich black Iowa mud in a right-of-way ditch, sinking up to my hips in the ooze. Boy, now I really did get scarred! Caught in the mantrap with boxcars about to rain all over me. I abruptly lost all expectation of attaining a ripe old age.”

“As thoughts of my past life flashed through my brain, I tried to remember a boyhood Sunday school prayer. Then came the miracle. Stillness descended over the scene. The writhing of the train had stopped just at the car on which I had been standing. Not a sound broke the silence except for the pops of the engines, which I imagined were slowly sinking in the mud of the Iowa River, or were at least on their sides down in the fill.”

It must have been someone’s lucky day that day. Mr. Brunet’s failure to hop on the gondola car that fateful afternoon had saved his life.

His story of clearing the wreck continued. “At length we got the train of crippled cars back on its feet and started home for Marshalltown. It was a slow grind and seemed more torturous because we had been away for eight days. We were anxious to see our friends and families again and sink our teeth into real food.”

“As soon as I turned the engines into the roundhouse lead, I made a dash for the yard office and called my wife. She was overjoyed to hear my voice.”

“’Hurry home George!’ she said, ‘I’ll make your favorite lunch.’”

“’My favorite lunch?’ I asked with a sudden dark suspicion. ‘What’s that?’”

“The answer came back:

‘Fried eggs of course, darling.’”

© 2020 Steamboat Rock Historical Society | All Rights Reserved

Powered by Hawth Productions, LLC